What is a correspondent bank? A correspondent bank is a bank that provides services on behalf of another, equal or unequal, financial institution. It can facilitate wire transfers, conduct business transactions, accept deposits, and gather documents on behalf of another financial institution.

Correspondent banking could arguably be one of the most difficult business lines for AML (anti-money laundering) suspicious activity systems to monitor, but are there any opportunities for improvement and increased sophistication? The fundamental conundrum for compliance departments monitoring correspondent banking payment activity is that they must rely on the respondent bank’s AML policies, procedures, controls and technology systems to identify suspicious activity and to take appropriate steps to mitigate the risks, which could result in the respondent bank ending relationships with nefarious customers. In order to remain proactive, banks providing access to the U.S. financial markets via correspondent banking relationships should consider increasing the sophistication of how they detect suspicious activity based on what information is already contained in the wire payments and existing watch lists.

If correspondent banks are monitoring their customers’ customers, then it requires several parsing algorithms to determine several key pieces of information such as:

- Creating pseudo account numbers based on the originator and beneficiary names and addresses referenced in the wire payments.

- Extracting country codes for the originator of the payments and, when available, for the beneficiary as well.

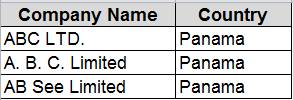

For example, if three different payments are processed by the correspondent bank and the originator of the payment has a similar name as shown in the Company Name column in the table below, then how can the system determine if the company in the wire payment is the same entity or not? The purpose of this article is not to delve into the wire payment parsing algorithms for account and country extraction, but the assumption is that a correspondent bank will have some type of system deriving this information before it makes it way to the suspicious activity monitoring system.

In general, most suspicious activity monitoring systems detect patterns based on the amount, velocity of activity and associated risks with the payment, such as country risk. For example, if the company ABC LTD. sent 10 wire payments between the range of $50,000 and $250,000 to five different entities all located in high-risk jurisdictions over a relatively short time period, then this could be a scenario worthy of an investigation, if no other information was available on the originating customer. One key risk indicator missing from this scenario, but part of most traditional suspicious activity monitoring systems in which the customer is on-boarded by the bank directly, is the customer risk rating. The correspondent bank only has information on the wire payment itself, but no information regarding the underlying originator and beneficiary of the payment. All payments are filtered through the bank’s sanctions monitoring tool, which will trigger alerts based on specific scenarios such as SDNs (specially designated nationals), but most monitoring systems do not integrate the respondent bank’s customer risk due to a lack of information.

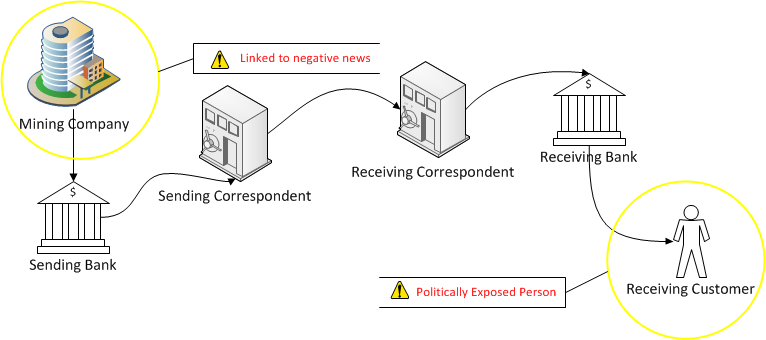

However, watch lists could be leveraged to detect PEPs (politically exposed persons) and entities associated with negative news, which could range from fraud and embezzlement to possible links to terrorist groups. The watch list algorithm could be designed to assign a probability score to any potential matches in the wire payments against the watch lists. Then a bank AML/fraud investigator could review the wire payment to confirm if the name matched against the watch list is the same entity. After the confirmation from the investigator, any future payments by that entity would be under increased scrutiny and could be treated as a high-risk customer, which generally triggers alerts more often than do low-risk customers.

Negative news searches and PEP identification would be completed during most standard AML investigations if the entity triggered an alert, but the real value of this algorithm would be to identify high-risk entities “below-the-line” or under the minimum alert score threshold that aren’t triggering actual alerts.

Correspondent banks could also gather valuable information about their respondent banks by establishing ratios for banks with high concentrations of PEPs and/or entities linked to negative news relative to the bank’s size or payment activity. These metrics could be referenced during the correspondent bank’s de-risking process, which may not always be intuitive because banks in low-risk jurisdictions could be initiating high-risk payments and, conversely, banks in high-risk jurisdictions could be initiating lower-risk payment activity.