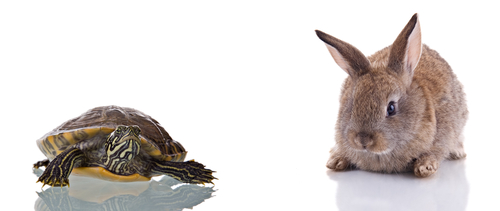

Aesop’s Fables is a collection of tales by the Greek storyteller Aesop. We don’t know the true intent of Aesop’s stories since they were translated in early 1900s England by the Reverend George Fyler Townsend and Sara Cone Bryant. We do know that each of the modern day translators intended the fables to be stories for young children to teach them about life lessons.

The stories are simple to understand and use human and animal characters to describe how to make the right decision when faced with situations of uncertainty and complex ethical dilemmas. Most adults have heard of “The Boy who Cried Wolf” and “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” which teach lessons of telling the truth and the merits of thrift and hard work.

Aesop’s Fables describe a simplified world where the protagonist learns his or her lessons the hard way. We can all enjoy these lessons and feel satisfied that we have been responsible parents by reading them to our children! However, as our children grow older, life gets in the way and these lessons fall by the wayside. More importantly, we learn that decision making is more complex than the stories in Aesop’s Fables. While they may serve as a good guide, fables are not useful in dealing with the fast pace and increasing complexity of today’s real world. This may be one of the reasons these fables are increasingly lost to history’s dustbin.

Unfortunately, many GRC and risk professionals unknowingly use risk frameworks as Aesop’s Fables. We believe that if we simply tell our employees stories about the hard lessons learned by the unwitting protagonists in the story, they will learn what not to do. No one lives their lives by children’s fables and it is equally unlikely that business leaders will manage their organizations by the fables embedded in a risk management framework. Yet this is what we expect to happen!

Isn’t it time that we look beyond the simplicity of fables and lessons learned to advance the practice of risk management? The best analogy is with 17th century medicine. The best doctors who practiced in the 16th and 17th centuries did not know what happened inside the human body. Most of the remedies were based on observation, theory and – worst of all – whether the patient died under their care. It wasn’t until one doctor dared to think differently and look outside of medicine to learn how to diagnose problems inside the human body.

In the 17th century, wine makers would routinely thump their barrels of wine to determine whether it was full or evaporation had occurred as the wine aged. An enterprising doctor decided to see if he could diagnose congestive heart failure during which the lungs filled with fluid. By rolling up sheets of paper and thumping on the chest of patients this doctor learned to dismiss conventional wisdom and treat his patients using analytical thinking about the risks to his patients’ lives. Advances in medicine evolved slowly as physicians learned to look beyond the myths of the day about human illness and to develop better diagnostic tools for managing risks.

Shouldn’t risk managers think more like scientists or physicians? The answer is a resounding YES! Risks, like human illness, can lie just beneath the surface. The presentation of a symptom of a persistent problem may require a variety of tests to confirm an accurate diagnosis. Medical diagnosis uses a variety of approaches through a process of elimination to determine possible causes of medical risks. Risk probabilities are assigned to the accuracy of the causes and there is an understanding of residual risks assumed by the patient in proceeding with a prescribed course of action. These risks are acknowledged with the understanding of the limits of a successful outcome.

If we cannot guarantee risks in life and death decisions, why do we expect to do so in business?

Risk management, like Aesop’s Fables and early medicine, has been around for centuries. Unfortunately, the diagnostic tools to manage risks are still in the early stages of sophistication. Many risk professionals still diagnose their corporate patients based on a set of symptoms, without understanding the root causes underlying the illness.

Will we continue to believe in fables or will we begin to think like modern day diagnosticians and attempt to understand what is needed to look beneath the surface?

James Bone’s career has spanned 29 years of management, financial services and regulatory compliance risk experience with Frito-Lay, Inc., Abbot Labs, Merrill Lynch, and Fidelity Investments. James founded Global Compliance Associates, LLC and TheGRCBlueBook in 2009 to consult with global professional services firms, private equity investors, and risk and compliance professionals seeking insights in governance, risk and compliance (“GRC”) leading practices and best in class vendors.

James Bone’s career has spanned 29 years of management, financial services and regulatory compliance risk experience with Frito-Lay, Inc., Abbot Labs, Merrill Lynch, and Fidelity Investments. James founded Global Compliance Associates, LLC and TheGRCBlueBook in 2009 to consult with global professional services firms, private equity investors, and risk and compliance professionals seeking insights in governance, risk and compliance (“GRC”) leading practices and best in class vendors.