with co-author Daniel Herd

Identifying and managing emerging risks is perennially a top concern for most organizations, as an unforeseen threat can quickly impact company operations in a significant way. CEB research shows that progressive companies regularly scan for new risks and embed systems and processes that enable them to detect risks early. They also work to uncover risks by encouraging contrarian thinking and questioning strategic assumptions.

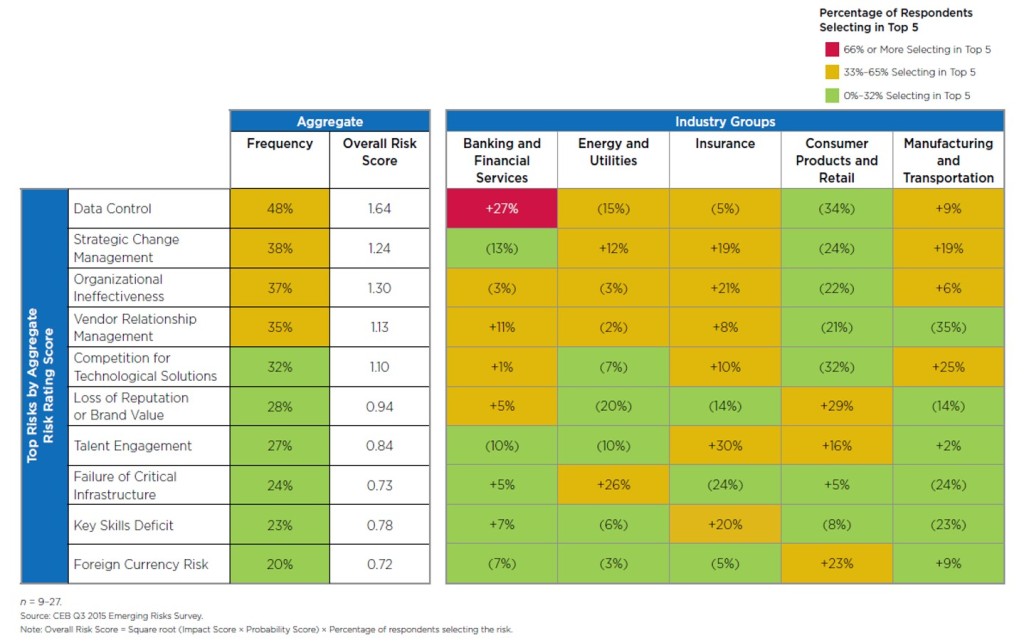

With this in mind, every quarter, we survey senior executives in risk, audit, finance and compliance at leading companies on key emerging risks and the potential impact, probability and velocity for their organizations. The dashboard in Figure 1 captures the percentage of survey respondents that select a given emerging risk as one of their top five concerns, giving us insight into which emerging risk events are the most important to companies.

Emerging? Emerged? Enterprise? What’s the Difference?

We are often asked how we define “emerging risk” and about the difference between an existing and an emerging risk. While some consider this to be more semantics than substance, the confusion that often arises in conversations about new risks warrants a specific definition. For example, some clients we work with wonder why we haven’t included cybersecurity on our list of emerging risks, despite its prominence as a top risk for most companies. However, is cybersecurity really a new risk? Can we reasonably say that it is truly emerging, or has it already emerged to be front-and- center for most organizations?

Based on our conversations with ERM leaders at more than 300 companies, we have concluded that an emerging risk takes the form of a systemic issue or business practice that has either not previously been identified or has yet to cause significant concern. Given that the complexity of emerging risks often leads to a high level of uncertainty, an emerging risk frequently leads to the implementation of an interdisciplinary risk treatment plan.

Data Control

Data control is a risk that has recently risen to the top of many leaders’ lists of concern. Cases of cyber hacking and fraud have expanded national security priorities beyond traditional national security efforts into the private sector. Recent hacks of the OPM, IRS and CIA Director have put a spotlight on the hacking attempts organizations in the private sector face on a daily basis and the potential for national security concerns that could result (imagine a hack of a nuclear power plant). This has led the government to expand national security priorities and begin mandating heightened and more formal cooperation between the public and private sector in order to facilitate the tracking of potential threats.

However, many in the private sector have resisted these efforts, with some arguing that collaboration should not come at the expense of customers’ privacy. Further, some companies have raised concerns that close cooperation between the private sector and U.S. government authorities could be perceived by foreign investors and authorities as threats to their own national security. This leaves these firms with higher barriers to market entry and a tougher regulatory environment.

The concerns surrounding data control have never been more prevalent than they are today, especially with the recent U.S. Senate passage of the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA), which is expected to be signed in to law in early 2016. CISA authorizes private entities to share information about cybersecurity threats and defensive measures with the federal government. There are a number of protections for companies in the legislation that encourage them to be an active participant in this information sharing. However, while broad consensus has emerged in the last few years regarding the need to enhance sharing of cybersecurity threat information both within the private sector and with the government, these protections largely do not address the concerns of foreign investors.

What the Best Companies Do

Although in many cases companies are prohibited from disclosing their cooperation with government authorities, leading companies are transparent about information disclosure and work with government authorities to ensure new regulations requiring private sector cooperation are reasonable. They also empower employees to participate in public debate about key issues, such as data sharing, that could adversely affect the company. Progressive organizations also track legislation and use a legislative response strategy that evaluates, shapes and prepares them for the consequences of legislative change.

While some organizations worry that the increasing role of government in controlling data flows could lead to resistance among the private sector, foreign partners and investors, there is an opportunity to influence legislation and comply effectively. Progressive companies take steps to ensure that, when it appears that security and privacy concerns are on a collision course, a marriage of common interests is still possible.

Matt Shinkman is Practice Vice President for

Matt Shinkman is Practice Vice President for