Popular among Web3.0 companies, decentralized autonomous organizations, or DAOs, lack many of the traditional elements of legal business entities. But attempts to fit DAOs into traditional structures is having a perhaps-unintended consequence: Some of these organizations may be subject to the enhanced beneficial ownership reporting requirements coming early next year. Jeanne R. Solomon and William E. Quick of Polsinelli dig into this issue.

The application of the recently enacted U.S. Corporate Transparency Act to decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) raises novel legal issues. DAOs are a relatively new type of business association (often existing as a common law partnership) that have not been formed as traditional legal entities. As such, they lack statutory governance and liability protections for their participants (though this is rapidly changing).

Recent initiatives and legislative enactments, however, have sought to fit DAOs into traditional entity structures to promote protections for those utilizing the DAO model. One consequence is that DAOs operated through business entities will need to comply with the CTA’s beneficial owner disclosure obligations. Beginning Jan. 1, 2024, the CTA requires reporting to FinCEN of individuals’ direct and indirect beneficial ownership in reporting companies operating in the U.S.

How does the CTA relate to the rapidly evolving legal landscape relating to DAOs?

CTA overview

A “reporting company” is a corporation, limited liability company, limited partnership, business trust or other “similar entity” that is created or registered to do business in the U.S. through a document filing with a secretary of state.

Exempt entities include heavily regulated businesses, such as SEC reporting issuers, registered broker/dealers, registered public accounting firms, venture capital fund advisers, utilities, financial institutions, insurance providers and Section 501(c) tax-exempt nonprofits.

An additional exclusion pertains to “large operating companies,” which meet all three of the following factors: (a) have a U.S. physical commercial street address, (b) have 21 or more full-time employees and (c) have more than $5 million in annual gross receipts or sales as reported in the prior year’s U.S. federal tax filing. Also excluded are wholly owned subsidiaries of an otherwise exempt entity.

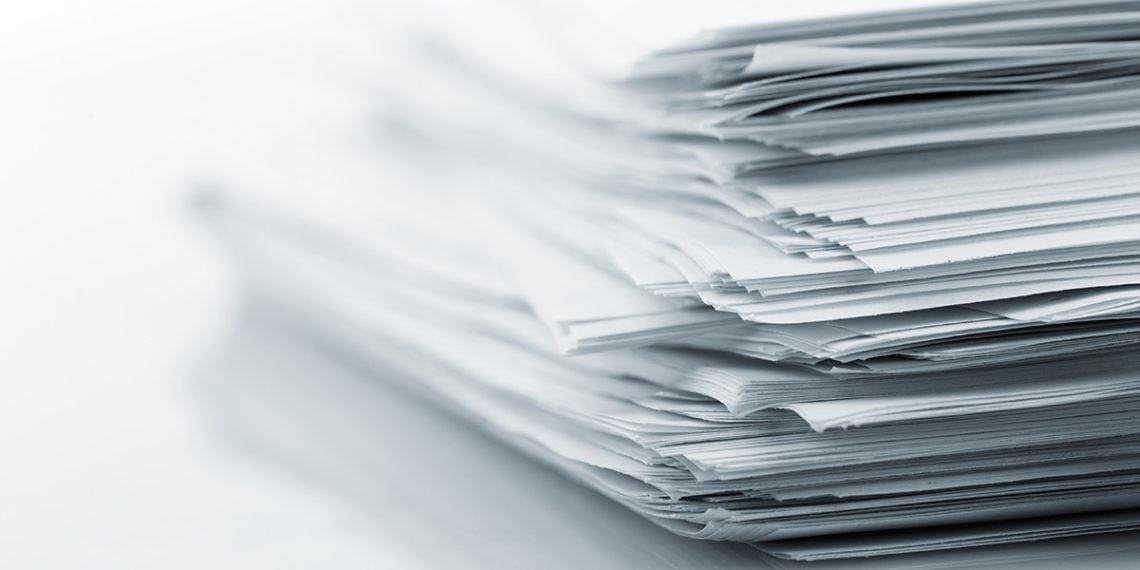

Beginning next year, reporting companies must begin reporting into the Beneficial Ownership Secure System (BOSS) operated by FinCEN. The BOSS may be accessed by federal, state, local and tribal law enforcement and financial institutions (with their customer’s consent). BOSS reports filed under the CTA are not accessible by the public and will be exempt from search and disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) or similar laws.

Beneficial owner information to be reported to FinCEN includes a person’s name, birthdate, address and an image of a government-issued identification (including the person’s photo). Beneficial owners include both individuals with substantial control over the entity and those who directly or indirectly own 25% or more of the equity in the entity. Every reporting company has at least one person to report. A beneficial owner’s refusal to provide disclosure information will result in such noncompliance being “red flagged” for FinCEN.

Existing companies formed by Dec. 31, 2023, will have until Dec. 31, 2024, to make their initial BOSS filing, while companies formed starting Jan. 1, 2024, will have only 30 days to make their initial BOSS filing. All businesses will have only 30 days to file any correction or change to previously reported information. Fines and penalties for non-reporting or false reporting can be steep.

Corporate Transparency Act: What Is It, and How Will It Affect Small Companies?

The 2021 Corporate Transparency Act included new reporting requirements that represent the most significant change in the formation of corporations in decades, and while it’s clear that the White House intends to use FinCEN regulations as part of its anti-financial crime pursuits, it may not be clear what that means for small companies.

Read moreDetailsOverview of DAOs

A DAO is an association of persons represented in part by rules encoded as a transparent computer program, usually controlled by the participants’ association and not influenced by a central governance body. Blockchain technology (a decentralized, digital ledger) allows for managing these organizations by decentralized autonomous means, often including issuing a proprietary cryptocurrency or digital asset.

A DAO is set up by programming the desired organizational structure onto blockchain technology by “smart contract” (self-executing contract), under which pre-programmed code sets forth the basis of the DAO’s decision-making structure and its governance. The smart contract will often serve as a de facto governing document. A DAO typically fundraises by issuing tokens for cash or other consideration, with tokens typically allowing for voting rights to make rule changes and take other actions.

DAO members may view DAO transactions on the blockchain (including a timeline of all contributions to the DAO and use of its funds). Purchasing DAO tokens is usually done on decentralized platforms, such as Uniswap or Lido, or directly through peer-to-peer transactions. DAO tokens are minted or issued, and once those tokens have been sufficiently distributed there is typically a “hand-off” event where the DAO’s token holders take over its decision-making from the original token issuers.

While DAO voting power is usually tied to the relative percentage represented by owned tokens to total tokens, sometimes voting is set up as “one vote per member” or as “quadratic” (for example, weighted by strength of preference). As of June 2023, there were reportedly approximately 2.5 million active voting DAO members worldwide and almost 7 million DAO governance token holders worldwide.

Current legal framework

As of spring 2023, only four U.S. states (Tennessee, Utah, Vermont and Wyoming) recognized DAOs, with various other states (including New Hampshire) considering legislation. Many DAOs also form as Delaware LLCs and set forth governance and operations in the operating agreement. State cooperative law statutes may also provide a framework (e.g., Colorado’s Uniform Limited Cooperative Association Act or the New York Cooperative Corporations Law), as might alternative structures for nonprofit or social enterprise DAOs, such as “benefit LLCs.”

Legislation has been introduced in California that would modify existing DAO unincorporated association law. As of 2022, the Republic of the Marshall Islands approved legislation recognizing DAOs as limited liability companies. Other popular countries for DAOs include the Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Gibraltar, Liechtenstein, Panama, Singapore and Switzerland (some of which allow formation of bridge-type entities like foundations or cooperatives).

Certain issues and constraints

DAOs’ challenges, constraints and risks include those relating to governance (including voting by rough consensus, rage-quitting and coups or hostile takeovers by members), enforceability of contracts (including legal standing and owning assets), infrastructure/scaling, treatment as securities, intellectual property ownership, application of bankruptcy and insolvency rules, proper taxation, procuring insurance, antitrust, fraud/error risk, cryptocurrency risks and dealing with KYC and AML rules (like the CTA).

How CTA may apply to and impact DAOs

The CTA assumes that a reporting company is a legal entity with a system of beneficial ownership and governance that a DAO may not possess. Traditional partnership-based DAOs will not fall within the CTA’s purview; but those DAOs subject to secretary of state-filed formation are considered legal entities in states having DAO legislation. Such DAOs will need to focus on CTA compliance.

The CTA’s reporting requirements will be particularly burdensome for DAOs given their member and control structure and operating framework. DAOs do not have managers, directors or officers, and determining the 25% ownership threshold or persons with “substantial control” may need to be made within each “member” rather than among the DAO members as a whole.

Further, if the DAO is considered to be a member-managed LLC under state law, each member would need to report beneficial owner information. Proper formation of DAOs in a way that is mindful of CTA compliance will require sophisticated formation and operational advice and counsel. Such challenges may drive DAOs away from registering (or staying registered) in states if they deem that such legal status will impose reporting obligations with which they cannot legally comply.

FinCEN has addressed non-traditional entities (like DAOs) with advice that “substantial control” includes “control exercised in novel and less conventional ways.” “It also could apply to the existence or emergence of varying and flexible governance structures, such as series limited liability companies and decentralized autonomous organizations, for which different indicators of control may be more relevant.”

The CTA applies to state-formed DAOs notwithstanding that FinCEN currently is unsure of how the CTA applies to DAOs.

The CTA does not address matters specific to a DAO’s unique ownership and governance structure, such as whether membership through token ownership constitutes “beneficial ownership” for CTA purposes. Realistically, without a governing body and management, it will be difficult for a DAO to name a CTA compliance person. As such, DAOs required to comply with the CTA will need to address these considerations in their structure and operations. Wrapping DAOs into traditional legal structures has historically exposed DAOs to certain reporting requirements (e.g., a Vermont “BBLLC” must make additional disclosures in its formation documents, including a mission statement and stating voting procedures and blockchain technology to be used), which subjects such DAOs to certain compliance protocols. Those requirements and protocols have now been expanded to include CTA compliance. Using “traditional” DAO parameters to regulate these non-traditional businesses may be incompatible with DAOs’ innovative and ever-changing nature and the “autonomous” aspect of DAOs’ nature. DAOs may need to monitor evolving CTA guidance as the CTA rollout continues.

DAOs that are legal entities or wraps

A DAO organized as a legal entity in a state that recognizes an entity structure may have an easier time with CTA compliance (or may face a conundrum as a legally recognized entity without directors, officers, managers or “members” to track CTA requirements). To the extent possible, such a wrapped entity DAO should set up compliance protocols in its governing documents, including point-people for initial CTA filings and amendments and tracking requirements and ongoing compliance. The CTA expressly prohibits “blank stock” and anonymous reporting company ownership, in direct opposition to most DAOs’ key compelling feature — anonymity. Since DAOs typically operate through the blockchain and smart contracts, structuring a DAO to adopt procedures to require substantial control and beneficial owner disclosure of personally identifiable information may be problematic (or unrealistic).

Takeaways

DAOs operated as common law partnerships with vicarious participant liability (i.e., the traditional model) do not face CTA exposure. DAOs operated as or through business entities established through state law filings (with attendant defined governance structure and limited participant liability) will be required to comply with CTA requirements. The inherent characteristics of DAOs and blockchain technology will make achieving CTA compliance challenging.

Proper formation and operation of DAOs, in a way that is mindful of CTA compliance, will require sophisticated advice, counsel and governance documentation. Because DAOs traditionally self-govern and self-regulate by their participants, it is possible that “burdensome” CTA compliance requirements and rigid methods of state regulation (required for limitation of liability) may further incentivize self-regulation in the DAO industry. The CTA compliance requirements may further the perception of the U.S. as an unfavorable environment for developing blockchain and DAOs, pushing DAOs toward countries with laws that are perceived as more welcoming.

Jeanne R. Solomon

Jeanne R. Solomon William E. Quick

William E. Quick