The History of FCPA Enforcement, Part 2

In Part 1 of this two-part series on the history of the enforcement of the FCPA, Anne Eberhardt discussed some of the factors that led to its creation. In this second part, she describes how the FCPA evolved into one of the most feared law enforcement tools.

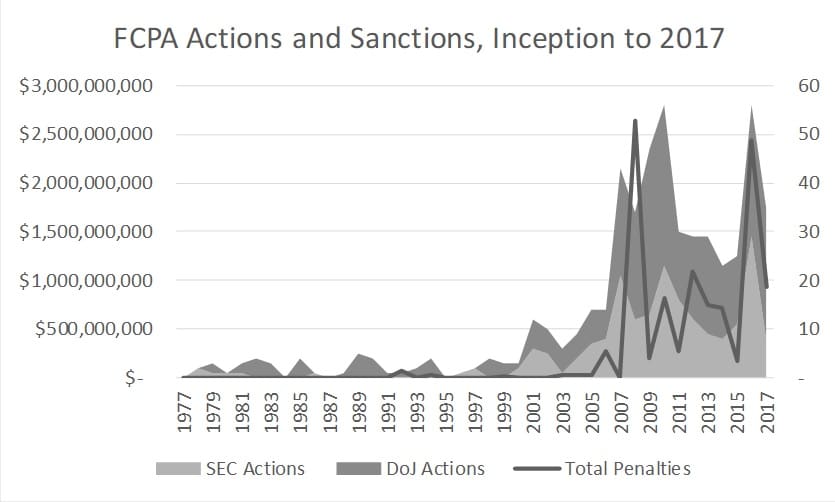

The FCPA was signed into law in December of 1977. During the 40 years that followed, ending in 2017, the SEC and the U.S. Justice Department collected about $10.6 billion in fines and penalties under more than 520 enforcement actions. About $10.3 billion – or approximately 98 percent of the total –came from the 421 enforcement actions pursued from 2006 to 2017. The chart below provides a vivid illustration of the explosion of FCPA enforcement actions and sanctions.[1]

Why did a law prohibiting U.S. companies from engaging in foreign bribery, passed in the 1970s, get dusted off in the mid-aughties to become one of the most feared weapons wielded by the U.S. government, causing symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress disorder among senior leadership and compliance officers in some of the largest and most powerful companies in the world?

A number of unrelated factors seem to have contributed to expanded enforcement of the FCPA, which followed a period of shocking corporate financial scandals and a geopolitical restructuring after the end of the Cold War and the September 11 attacks. As information technology exploded, so did the tools for investigating, monitoring and even leaking corporate wrongdoing. And government itself changed as management tools for measuring accountability became normalized throughout the federal bureaucracy.

Corporate Integrity Crisis

In 1976, it might still have been possible for a U.S. official to argue with a straight face, as the Treasury Department’s Assistant Secretary for International Affairs Gerald Parksy did, that “[t]he vast bulk of our firms conduct their businesses ethically and completely in accord with the laws of the United States.”[2] By 2002, however, following the accounting scandals of Enron, Tyco and WorldCom and the collapse of the auditing firm Arthur Andersen, there was a deep crisis in confidence in the integrity of corporate officials.

In response, Congress passed the Sarbanes Oxley Act, or “SOX,” in 2002, which included requirements that top managers of SEC registrants declare their responsibility for creating internal controls, draw conclusions regarding the effectiveness of those controls and report any incidents of control failures. Furthermore, SOX provided whistleblower protections to those within companies who report corporate wrongdoing.

In other words, SOX created the obligation for management, as well as incentives for whistleblowers, to report any kind of corporate violations, including those related to the FCPA. Moreover, the USA PATRIOT Act, passed in 2001 following the September 11 attacks, increased scrutiny of cross-border transactions. Those that had the whiff of corruption about them were now suddenly more likely to come to the attention of regulators.

Even as the executives of Enron, WorldCom and Tyco were being tried for corporate wrongdoing, ever more spectacular accounting scandals exploded onto the headlines, including those of AIG, HealthSouth, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Revelations of widespread corruption during the implementation of the U.N.’s Oil-for-Food Programme that were uncovered after the 2003 invasion of Iraq further smeared the reputation of American business leaders.

But it was after the financial crisis of 2008 and the accompanying bailouts of nearly the entire financial system that enforcement actions accelerated with what might even be described as a vengeance. No longer were regulators willing to accept that corporate actors, left to their own devices, could be expected to behave ethically.

The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, which primarily addressed financial services companies, expanded upon the whistleblower protections of SOX and provided financial incentives to those who report wrongdoing that leads to successful enforcement actions, including violations of the FCPA.

The Data Revolution

The turn of the millennium was accompanied by an explosion in electronic data storage and processing capability. The tools routinely used in FCPA investigations, such as electronic document review and data analytics, were simply not available before data storage and search capacities began accommodating them in the mid-2000s.

As analytics software became more user-friendly, programs such as Microsoft Excel and Access provided opportunities for a greater pool of talent to be deployed in large-scale investigations. With the Windows 2010 release, Excel expanded from about 64,000 rows of data to more than 1 million, allowing armies of freshly minted Excel Jedi to sort, filter and pivot away through massive accounting system downloads.

And, as storage and data analytics capabilities increased, so did regulators’ expectations of what organizations could and should do to monitor their activities internally.

Government Accountability

One of the important trends in government during the past generation has been the idea that it should (a) shrink and (b) become more accountable. More than one management consultant, describing their expertise in terms akin to a “blue belt in Eight Beta,” persuaded government agencies to hand over large amounts of cash for training in process optimization and identifying key performance indicators for measuring organizational efficiency, effectiveness and economic performance.

Once government agencies adopted numeric measures to demonstrate their success, it’s not difficult to imagine that an administration official might boast, say in 2010, that the SEC and Justice Department had initiated 56 FCPA-related actions and collected $835 million in fines and penalties, making it (at the time) the largest year ever for enforcement actions and the second-largest year for the dollar amount of fines and penalties assessed.

Globalization

But perhaps no single factor has contributed to the increase in FCPA enforcement than the rise of a globalized economy. When the Soviet Union collapsed and the doors to trade with China were opened, many of the restrictions on the flow of capital disappeared. While, in the past, bribe-paying might have been the domain of only a handful of oil companies and defense contractors, many more companies are now cultivating business opportunities in places where bribery is culturally more acceptable.

Perhaps, then, enforcement of the FCPA exploded simply because more companies found themselves invited to bribe public officials in places such as China, Malaysia, Gabon, Kazakhstan and Argentina.

The Future of the FCPA

It is worth asking whether the aggressive enforcement of the FCPA has had the desired effect of reducing foreign bribery. Have U.S. companies simply lost ground, as critics often argue, while investment shifts to companies based in nations outside the reach of the FCPA? Will more foreign-based countries think twice before seeking access to U.S. capital markets? Will those that are currently SEC registrants follow the example of Eberhard Reichert’s former employer and deregister from the SEC, as Siemens did in 2014?

As the FCPA embarks on the next 10 years toward its 50th birthday, will the United States make any significant changes to its enforcement of this law? The current administration has sent signals that it wishes to focus more on prosecuting individuals and less on extracting eye-watering fines and penalties from their employers. Other nations have now passed laws similar to the FCPA, and there seems to be a global revolution brewing as citizens increasingly feel empowered to express their antipathy toward corruption at home.

But it seems unlikely that there will be a return to the 1980s, when there was far less apparent interest in enforcing the FCPA.

[1] The Stanford Law School Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Clearinghouse, in Collaboration with Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Charts & Graphics, Sanctions and Proceedings charts, http://fcpa.stanford.edu/chart-penalties.html, and http://fcpa.stanford.edu/statistics-analytics.html, accessed June 2, 2018

[2] The Story of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (December 5, 2012), Ohio State Law Journal, Vol. 73, No. 5, 2012, pg. 937. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2185406

Anne Eberhardt, CFE, CAMS, is a Senior Director in the Valuation and Litigation Consulting practice at

Anne Eberhardt, CFE, CAMS, is a Senior Director in the Valuation and Litigation Consulting practice at