Disruption and the unexpected are now the norm for many industries. Accordingly, more clarity is needed around framing the risk conversation in the C-suite and the boardroom.

Remember when your parents took you to the zoo when you were a kid? I bet most of you had some animals in mind you wanted to see. As Dorothy, the Scarecrow and the Tin Man exclaimed in the forest on the way to Oz, perhaps for some it was “lions and tigers and bears, oh my!” For others, maybe it was elephants, giraffes or crocodiles. As for me, it was the gorillas.

In the zoo of risk, there are many kinds of animals to see in the normal course of managing a business day-to-day. There are also creatures we do not want to see — disruptive risks that we know we will inevitably cross paths with no matter what we do. If we have learned anything in recent years, it is that disruptive risks are the ones that are most likely to threaten the viability of a company’s strategy and business model.

In 2018, the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) issued a report on the board’s oversight of disruptive risk.[1] (If there were any doubt that disruption is the order of the day, it was dispelled with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.)

Bottom line, smart boards and executives have come to terms with expecting disruptive change. The most important recommendation in the NACD report is the first:

The board, CEO and senior management need to develop an understanding of disruptive risks — those that could have an existential impact on the organization — and consider them in the context of the organization’s specific circumstances, strategic assumptions and objectives.

Other recommendations in the NACD report pertained to matters like allocating board oversight responsibilities for disruptive risks, periodically evaluating board culture, managing unconscious bias, CEO selection and evaluation, talent strategy, board-level risk reporting, director renomination, diversity and learning and sufficient agenda time for substantive discussions of the company’s vulnerability to disruptive risks.

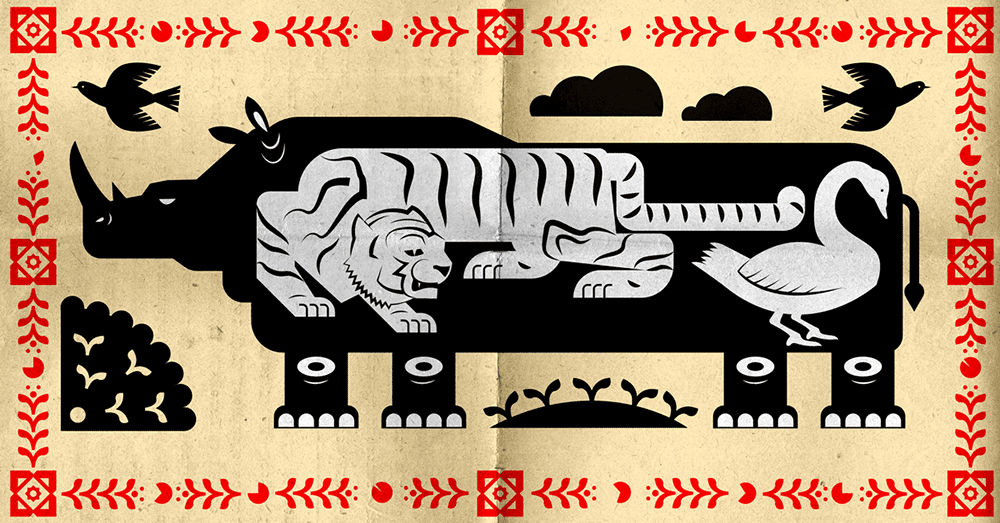

Regarding the first recommendation, the following three classifications — animals we do not want to see in the zoo of risks — offer insight in developing an understanding of disruptive risks:

- White elephants are “extant, existential risks that are difficult to address … because they are … situations fraught with subjectivity, emotions and loyalties … [the] classic ‘elephant in the room.’” Often related to culture and dysfunctional behavior, examples include poor top-down and/or bottom-up communications, aggressively dominant or unethical CEOs, confusing organizational structures, ambiguous decision rights, strategic disconnects from current and expected business realities, significant talent gaps, and toxic workplaces such as those requiring people to work in hazardous conditions, producing unsafe products or undertaking recklessly risky bets.[2] Theranos is a good example of a business model built on unsubstantiated claims and hype advanced by a CEO whose board trusted her too much for far too long.

- Gray rhinos are “highly probable, high impact threat[s]; [things] we ought to see coming.”[3] They loom on the horizon, and there is general understanding that it is a matter of when, not if, making robust response and contingency plans an imperative. The pandemic is a good example. Organizations often experience difficulty in evaluating these threats because the lens of relatively short time horizons constrains traditional risk assessments.

- Black swans are highly improbable catastrophic events that few, if any, see coming and that are often explained in hindsight as if they were predictable. Yet prior to occurrence, their causes and effects are not generally understood. Indeed, rare and extreme events equal uncertainty, which is exacerbated by blind spots with respect to randomness and particularly large deviations.[4]

So, the world in which businesses operate is a zoo consisting of white elephants, gray rhinos, black swans and whatever animal types one wishes to ascribe to the myriad other risks inherent in operating the business.

Outlier situations associated with normal, ongoing day-to-day business operations should be reported to senior management on an exception basis and, if deemed significant, escalated to the board. But the primary focus of management and the board should be on the critical enterprise risks and emerging risks, along with their unique disruptive characteristics.

In an environment of disruptive change, it is vital to build an innovative culture that facilitates resilience and agility in response to negative events with an emphasis on seizing market opportunities whenever they present themselves. To that end, following is a short summary of takeaways for executive management and the board:

Address white elephants with focused attention and decisiveness. Executive management and the board should foster the right tone in driving a commitment to sound governance, building trust within the organization, nurturing and preserving brand image, and fostering a diverse and inclusive culture and ethical and responsible business behavior. This tone starts with the board and the CEO. Directors should ask the tough questions and offer objective advice in dealing with whatever corrective action must be taken.[5] The CEO should stamp out dysfunction and own the tone at the top as well as the processes for driving alignment across the organization.

Encourage an agile and resilient culture and mindset that adapts to charging gray rhinos. Evolving customer preferences, digital transformation and acceleration, future of work and the workplace, new market entrants, supply chain congestion, changing laws and regulations, fresh cyber threats, increased focus on ESG performance and stakeholder expectations and ever-changing geopolitical dynamics all point to forthcoming change. Best be prepared and ready to pivot. Companies should organize for speed, keep an eye on relevant trends and industry developments, deploy data-informed approaches to understanding customer behavior, direct necessary changes to processes, products and services and invest in the talent that can make it happen.

Be an early mover in responding to black swans. Identify the most critical strategic assumptions, monitor continued validity of those assumptions over time, use “early alerts” to trigger timely warning of change and build discipline into the culture to act in a timely manner before knowledge of emerging opportunities and risks becomes common knowledge to most market participants.

Anticipate extreme but plausible scenarios. The bar of plausibility has lowered steadily over the years, and it is not “if” but “when” and “what if.” Consider velocity, persistence, response readiness and uncompensated risks associated with each scenario to guide the sense of urgency in formulating robust response plans and adaptive strategies that mitigate the impact of outcomes. To illustrate, it has been a long time since geopolitical issues have commanded attention in C-suites and boardrooms. Now that the war in Ukraine has created significant shortages in such commodities as grains, copper and nickel, we can be certain that various geopolitical scenarios will receive increased focus for some time to come.

Manage preconceived bias. Decision-making quality is compromised when data is structured to fit a preconceived view, reliance is placed on the smartest or most dominant people in the room, the past is extrapolated into the future, false security is drawn from probabilities, the limitations of consensus are ignored and efforts are made to manage toward a singular view of the future. Groupthink, a blame culture and avoidance of difficult conversations enable bias to thrive.

To illustrate, the 2011 tsunami in Japan, resulting in a nuclear catastrophe, raised an important question: Why rely on earthquake models based on limited empirical data and ignore geological evidence suggesting that waves over 20 feet higher than the models contemplated had occurred in the past? Was it unconscious bias to avoid further investments to protect the facility? Comfort with assessments of “extremely low” risk? Whatever, the decision by the company and its regulators regarding a random event represented a costly bet of the plant, the company’s reputation and — whether anyone realized it or not — the entire industry.

Beware of short-termism. While short-termism normally refers to an excessive focus on short-term results at the expense of long-term interests, it creates blind spots, too. Executives and directors see a different picture looking out 10 years instead of one to three years. For example, an oil and gas company executive may have difficulty ranking such risk issues as climate change, alternative products, carbon tax legislation and carbon use legislation as high-priority looking one year out but can readily see their relevance looking out longer-term, say 10 years. This explains why the annual risk profile published by the World Economic Forum (WEF) is so different from traditional corporate risk assessments. The specter of threats seen so clearly 10 years out is that they can either occur suddenly without warning today, or unforeseen developments can accelerate their occurrence, creating an edge for the most agile and resilient companies. Fossil fuels-based companies are experiencing that phenomenon now with the market’s sharp focus on climate change.

Following are suggested questions that senior executives and directors may consider, in the context of the nature of the company’s operations:

- Do we understand the company’s most significant disruptive exposures — the things that could destroy enterprise value that has taken decades to build — if we cling to the status quo and yet may offer opportunities to create significant value as well?

- Do we understand the critical assumptions underlying our strategy and business model and evaluate those assumptions with appropriate information from internal and external sources? Are scenario planning and stress testing used to challenge these assumptions, address “what if” questions and identify sensitive external factors that should be monitored over time?

- Does the organization have adaptive and experimental processes in place to address the opportunities and risks associated with disruptive change and drive innovation in its processes and offerings?

- Are we satisfied with internal reporting of forward-looking information about changing business conditions, opportunities and risks? Are early warning indicators linked to external factors reported timely? If not, how can we improve our reporting?

- Is sufficient boardroom agenda time set aside to engage management in robust discussions of disruptive risks and their implications to the organization’s strategy and business model? Are the takeaways from such conversations integrated with discussions of strategy setting? Do these discussions drive actionable steps to improve intelligence gathering and early alert systems?

References

[1] Adaptive Governance: Board Oversight of Disruptive Risks, National Association of Corporate Directors,” 2018, available at http://boardleadership.nacdonline.org/rs/815-YTL-682/images/NACD%20BRC%20Adaptive%20Governance%20Board%20Oversight%20of%20Disruptive%20Risks.pdf.

[2] “An Animal Kingdom of Disruptive Risks,” James C. Lam, NACD Directorship, January/February 2019, available at https://onboardspodcast.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NACD-Cover-Article_Animal-Kingdom_Lam-Jan-Feb-2019.pdf.

[3] The Gray Rhino: How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore, Michele Wucker, St. Martin’s Press, 2016, page 7.

[4] The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, second edition, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Random House Publishing Group, 2010.

[5] “An Animal Kingdom of Disruptive Risks.”

Jim DeLoach, a founding

Jim DeLoach, a founding