The rush to distribute billions in Covid-19 relief funds prioritized speed over scrutiny, creating unprecedented opportunities for fraud. Denise M. Barnes and Brian Irving of law firm Bass, Berry & Sims examine how enforcement has evolved from pursuing individual luxury car purchases to investigating systemic issues at fintech companies, while assessing how the new administration’s priorities may reshape recovery efforts.

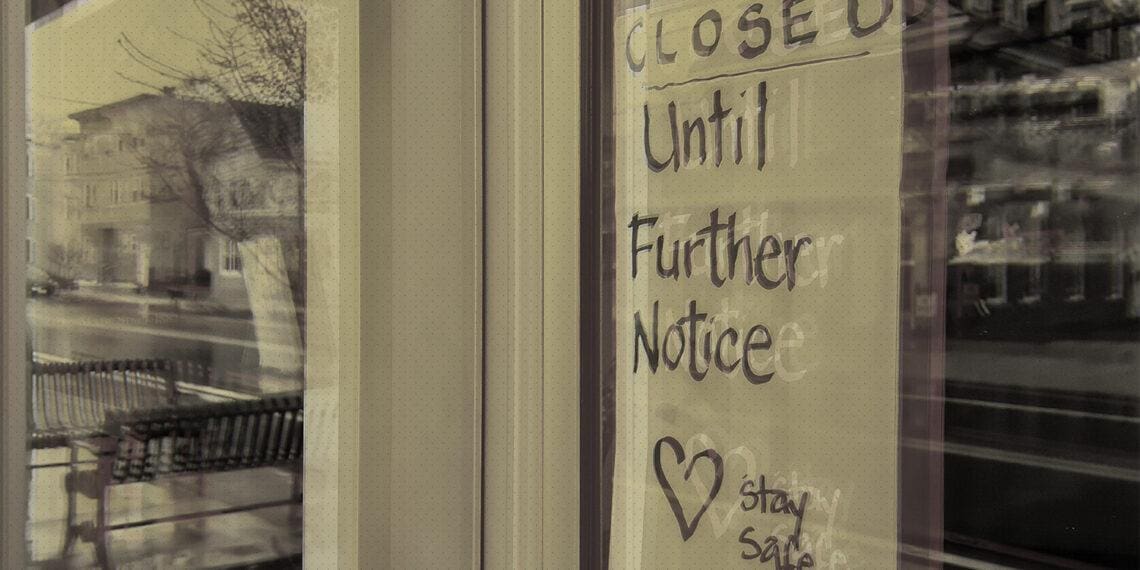

The federal government responded to the economic harm caused by the Covid-19 pandemic by pumping out trillions of dollars in pandemic relief through loans, grants and other funding. At the time, the government prioritized distributing aid quickly over policing compliance with funding rules.

Now that the pandemic has ended, the government has turned its attention to investigating and prosecuting pandemic-related fraud. Recent enforcement activities have targeted fintech companies and other corporate entities.

Enforcement response

In May 2021, the U.S. attorney general established a Covid fraud task force to coordinate the government’s enforcement efforts. The task force consists of multiple entities within the DOJ and other federal agencies.

Since the inception of the task force, enforcement related to pandemic fraud has intensified. In April 2024, for example, the task force announced that its efforts led to criminal charges against more than 3,500 defendants for losses of over $2 billion, civil enforcement actions resulting in more than 400 civil settlements and judgments of over $100 million and over $1.4 billion seized or forfeited.

These efforts, while substantial, are just the start. Total budgetary spending for the pandemic has amounted to over $4.6 trillion. And the Small Business Administration (SBA) estimates that $36 billion of $1.2 trillion in pandemic relief emergency program funds were obtained fraudulently. Some view the SBA’s estimate as too conservative, so the task force’s $2 billion recovery to-date represents only the start of the government’s efforts. The DOJ continues to pursue, investigate and resolve cases against individuals, companies and other organizations accused of engaging in fraud on government relief programs.

Early enforcement actions

Early fraud cases involved outlandish allegations of individuals purchasing luxury cars and yachts with pandemic funds: clear no-nos. The underlying conduct in those cases was, in most cases, criminal and involved extremely “bad facts.”

Recent cases have involved civil investigations, often regarding allegations about an individual’s or a company’s eligibility (or ineligibility) for a Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan or false certifications related to a company’s application. The government is continuing its efforts along those lines.

For example, in March 2024, the US elected to pursue a qui tam False Claims Act complaint in California against home health agency Allstar Health Providers and JMG Investments. The government alleges that Allstar and JMG defrauded the government by twice applying for and receiving PPP funds, despite certifying that they had not previously received loans.

These allegations originated from a whistleblower who used publicly available data and information to identify Allstar and JMG as potential fraudsters, which shows the scrutiny organizations are under. Though the government will likely still pursue cases like the one against Allstar, it is also focusing on more sophisticated pandemic-related fraud schemes.

The future of Covid-fraud enforcement

One government enforcement priority is fintech. In December 2022, a congressional subcommittee issued a staff report noting that many of the fintech companies charged with administering the PPP “appear to have failed to stop obvious and preventable fraud, leading to the needless loss of taxpayer dollars.” It’s no surprise, then, that the government has cracked down on fintechs that were responsible for underwriting pandemic-related loans.

A recent example is the Kabbage settlement. In May 2024, the DOJ announced a resolution with the now-bankrupt fintech Kabbage related to allegations that Kabbage knowingly submitted thousands of false claims for loan forgiveness, loan guarantees and processing fees to the SBA.

DOJ alleged that Kabbage systemically inflated tens of thousands of PPP loans, causing the SBA to guarantee and forgive loans in amounts that exceeded what borrowers were eligible to receive under the program rules. The settlement included an admission that Kabbage: (1) double-counted state and local taxes paid by employees in the calculation of gross wages; (2) failed to exclude annual compensation in excess of $100,000 per employee; and (3) improperly calculated payments made by employers for leave and severance. The DOJ claims Kabbage was aware of these errors as early as April 2020, but failed to remedy all incorrect loans that had already been disbursed and continued to approve additional loans with miscalculations.

Continued enforcement of fintechs and other nontraditional financial institutions is likely. Given this focus, an organization may consider engaging in a targeted review to confirm the eligibility of its borrowers and whether its Bank Secrecy Act/anti-money laundering controls were adequate, especially where the government has investigated a large volume of its borrowers.

There has also been a bevy of enforcement in the healthcare context, including an enforcement action against doctors and providers for false and Provider Relief Fund (PRF) fraud, manufacturers of fake Covid-19 vaccination record cards and individuals who fraudulently charged Medicare for over-the-counter testing kits, with losses exceeding $203 million.

Changing regulatory environment

The recent settlements with Kabbage and ReNew Health show that pandemic fraud enforcement efforts span industries and conduct. But irrespective of industry, companies defending these matters should consider whether the DOJ actually has a viable fraud case given that the reported misconduct occurred in an uncertain regulatory landscape. The relevant fraud statutes are intended to penalize bad actors that engaged in fraud, not companies that acted in good faith and made a mistake about the understanding of relevant guidance.

Pandemic funds were distributed, in many cases, in a hurried and crude way to meet the needs of business owners and employees who were trying to survive the worst of the pandemic. To penalize companies that acted in good faith is fundamentally unfair to business owners.

Companies that received or administered pandemic relief would do well to conduct a targeted review of their activities to ensure compliance with government rules and guidance and be prepared, where necessary, to defend against inappropriate government enforcement efforts.

Changing administration

While no one knows for certain how the new administration will approach fraud enforcement, there are signs that pandemic enforcement will likely continue to be robust. Historically, fraud enforcement generally remains above the political fray, as politicians on both sides of the aisle prioritize prevention and investigation of waste, fraud or abuse.

With the change in administration, we may see a temporary cessation in large-scale pandemic-related enforcement while the administration appoints new US attorneys and unveils its priorities. Most expect at least some slowdown in enforcement resulting from the appointment of more business-friendly prosecutors, but that remains to be seen.

Notwithstanding that fact, the Trump Administration has taken pretty aggressive public stances on cutting government waste and abuse — maintaining pandemic prosecutions seem to align with those positions, even if prosecutors remain focused on the more egregious conduct. Unfortunately, there seems to be enough of that to ensure that pandemic fraud prosecution continues.

Denise M. Barnes

Denise M. Barnes Brian Irving

Brian Irving

![FCPA Enforcement Is Changing; What Does It Mean for Compliance Programs? [Q&A]](https://www.corporatecomplianceinsights.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/doj-sign-on-building-350x250.jpg)