CCI columnist Mary Shirley doesn’t believe a compliance officer must be admitted to a state bar to be good at their job. And while this may buck conventional wisdom, a growing movement agrees. Here, she interviews Andrew McBride, who recently left his compliance chief role at Albemarle, where he built a program so effective that it scored a record-setting penalty reduction for an FCPA enforcement action — and not every person on his team had a JD.

Long gone are the days when compliance teams were cobbled together with people “voluntold” to take on the ethics and compliance portfolio without having raised their hand or having any particular interest in the area. In 2024, the discipline has evolved into a steadily growing workforce of compliance professionals, and you can even study compliance to concentrate on the practice area before entering the workforce. For example, I teach in Fordham’s compliance master’s degree program. We’ve come a long way since the discipline was established.

An ardent group of folks believe that a law degree should be a requirement of working in a compliance department, and many organizations only promote individuals to chief compliance officer (CCO) who do not have a compliance background but do have legal practice experience. I’ll be the first to admit that as someone who went to law school and is enrolled as a barrister and solicitor of the High Court of New Zealand, this old-school requirement has given me a leg up in the past, but this insistence on legal practice experience as a prerequisite for CCO jobs is perplexing.

In my heart of hearts, I know from working in this area for several years that it’s really not necessary to have a legal background to be effective at my job. And elitism and multi-way echo chambers are so distasteful, are they not? In fact, being fluent in legalese and refusing to write for laymen can be terribly detrimental to the modern-day practitioner whose work should be more user-friendly. I have taken to speaking out about the need for more diversity in compliance teams and advocating for my esteemed peers who happened to choose a different but no less useful educational path than I did.

As you can imagine, the guidance the HHS Office of Inspector General released in November came as a welcome vindication of my views. If you missed it, the voluntary guidance recommends that compliance and legal be separate and independent, that the general counsel not also hold the CCO title and that compliance should not be giving legal or financial advice.

At my previous employer, I worked within a compliance department of about 200 staff as we collaborated on our day-to-day tasks while also working toward getting through a multi-year Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) monitorship. While there were (and still are) several legally trained members of the team, I also admired the expertise and camaraderie of my colleagues from other disciplines, including the global CCO, who had a financial background.

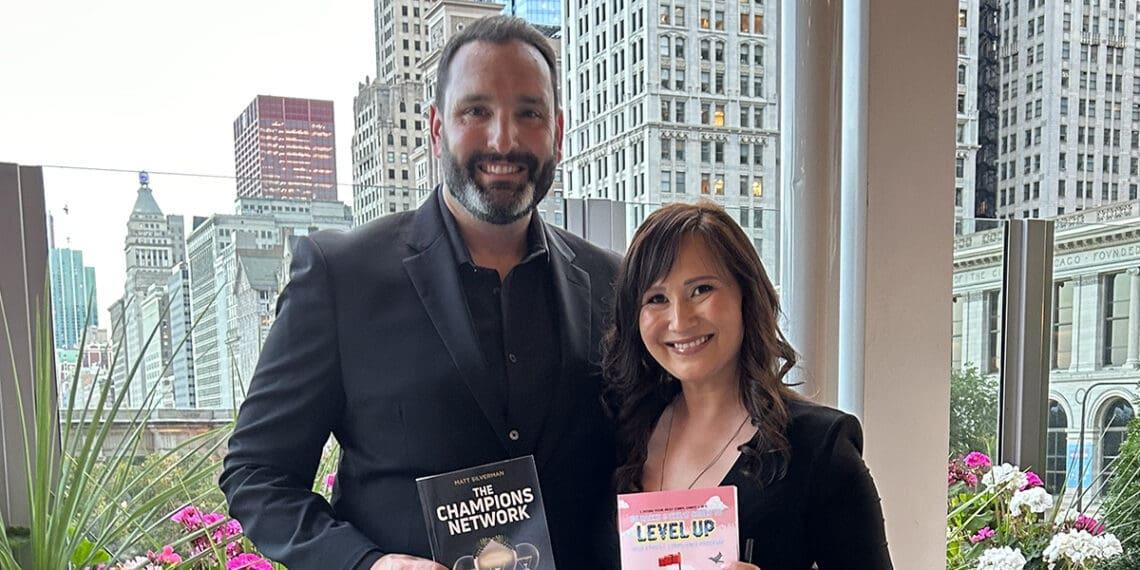

Until recently, Andrew McBride was in a similar position, as the chief risk and compliance officer for Albemarle Corp., a company that recently settled an FCPA investigation with the DOJ and SEC. While McBride is himself a lawyer, he brought together a multidisciplinary team that featured diverse skills. This is notable because in their enforcement actions, U.S. regulators publicly credited Albemarle’s ethics and compliance program as a key factor in securing the largest-ever percentage reduction in penalties for an FCPA investigation.

In this Q&A, which has been edited for clarity and length, McBride shares his tactical approach to building an effective and successful team.

Mary Shirley: This is a subject dear to my heart because it really is a case of people doing the right thing in the hiring process and doing right by the company to bring together a variety of skills and abilities. I know that this is important to you as well. As someone who is a lawyer yourself, why is it critical to look beyond fellow lawyers to staff your team?

Andrew McBride: In building ethics and compliance teams, I have always been guided by the resource requirements of the programs that I have built. The design of those programs has obviously been influenced by guidance issued by U.S. and other regulators but also the risks that my companies have faced.

To support a modern ethics and compliance program, a chief compliance officer needs a team with a diverse set of skills. Over the years, I have recruited compliance managers with forensic, accounting, auditing and supply chain experience. To support the team, I have hired people with communications, policy-writing and data analytics skillsets. I have seen other companies hire psychologists, which is really interesting.

And, yes, I have hired lawyers to be members of the team. But they have been hired due to their experience as compliance managers, not because they are lawyers. At larger companies, the legal department will often hire specialist compliance attorneys, such as antitrust or data privacy, but they are members of the legal department who support — but are not part of — compliance. In that scenario, there is even less reason to hire lawyers in the compliance team.

MS: What are some of the backgrounds and skillsets you found particularly important to deploy when getting a compliance program in shipshape while under U.S. government scrutiny?

AM: I’ve previously mentioned the importance of forensic, accounting, audit and communications skills. These are important irrespective of whether a company is being investigated.

In the context of a government investigation, I would emphasize the importance of a data analyst. When you are before a regulator, you are having to demonstrate that your program is working effectively. It is impossible to do that without data. A data analyst will work to secure access to the various types of data in ERP, HR and other systems and can store that information in a secure way and develop metrics and other data visualizations that can support internal and external reporting. They can also support transaction monitoring, investigations and audits.

Compliance Champions: How to Keep a Beloved Tactic From Going Stale

Ambassador, liaison or champion — whatever term you use, proper incentive is key

Read moreDetailsMS: What about as you look to the future and ethics and compliance continues to evolve?

AM: There are seismic shifts currently underway that are having a significant impact on the evolution of ethics and compliance programs.

Firstly, substantive scope. More and more compliance teams are assuming responsibility for sustainability-related compliance, carbon emissions tracking or modern slavery due diligence being two examples. Subject matter experts in these areas typically come from different professional backgrounds, but it is critically important that those programs are developed and implemented in a manner consistent with other compliance programs. Having those individuals be part of or connected to the ethics and compliance team can help.

Secondly, the relationship between compliance and enterprise risk management. As compliance officers assume responsibility for more and more areas of compliance, such risks cannot be considered in isolation of broader geopolitical risks at play (think modern slavery due diligence). At a minimum, compliance officers should be ensuring that they use the company’s broader enterprise risk management framework, but there is great opportunity for compliance officers to lead those broader risk discussions and even own the ERM process.

Finally, I go back to testing the effectiveness of compliance programs. It is not just regulators that need that assurance. The proliferation of compliance/sustainability standards and indices, and associated audits, means that companies need to be ready at relatively short notice to demonstrate to customers/investors that their program is working in practice. The collation and maintenance of that supporting information should not be underestimated, and, going back to our discussion on staffing, requires another type of skillset.

MS: What are some of the practices you adhere to in order to help encourage a wide variety of applicants for roles and reduce bias in the hiring process?

AM: I am a firm believer in hiring and developing compliance managers who are capable of undertaking all aspects of compliance (guidance, communications, due diligence, investigations, training, etc). This holistic scope of role means that I receive the wide variety of applicants that you reference. That said, when making my hiring decision, I will be guided by the risks/issues uniquely faced in that region. For example, if there is a proportionately higher number of investigations in the region, I might hire someone with more forensic experience.

Also, in my promotion of advertised roles, I will explicitly indicate that our search is not limited to a particular professional qualification, such as being a lawyer.

MS: What would your advice be to compliance practitioners who are searching for a new role and are facing job descriptions that repeatedly require a law degree to be considered for the role?

AM: Challenge the orthodoxy. In your cover letter, explain in constructive terms why you believe you have the skills for the advertised role. You are unlikely to be the only one, and the more people that make the point, the more likely the message will get through to recruiters for that and future roles.

MS: How can we encourage our peers to let go of old practices that aren’t serving the profession and reduce the number of jobs advertised requiring a legal education (and admission to a bar)?

AM: Articles like this! Seriously though, if you have a peer relationship with a company advertising for such a role, discreetly reach out and ask why it is being advertised as such. I also think recruitment consultants have a responsibility here to help educate hiring managers, especially general counsels, on why a legal qualification/education is not necessarily needed.