Gregory S. Kaufman and Amber S. Unwala of Eversheds Sutherland (US) LLP review enforcement activity by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) in 2018, discuss key enforcement actions and provide insight on what trends companies can expect to see in the year ahead.

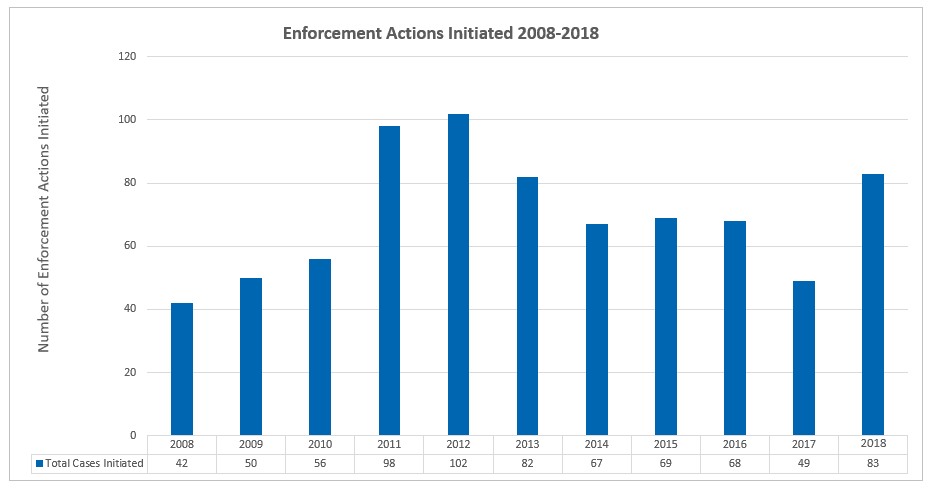

In 2017, the number of enforcement actions initiated by the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) dropped to the lowest overall number (49) since 2008.[1] This number was well below the average of 68 actions during the same time period. With fewer actions initiated, the civil monetary penalties also dropped from $748 million in 2016 to $334 million in 2017. However, fiscal year (FY) 2018 was a very different story for the CFTC. In the last year, the CFTC initiated 83 actions, with civil monetary penalties amounting to $897 million. The director of the Division of Enforcement, James M. McDonald, remarked that the past fiscal year was “among the most vigorous in the history of the CFTC.”[2] The overall number of actions initiated certainly support Director McDonald’s statement, but the overall numbers do not tell the whole story.

This article analyzes enforcement activity in 2018, identifies CFTC trends and priorities and peers into the future to spot potential areas of focus in the coming year.

Putting FY 2018 in Context

In order to put FY 2018 into context, it is helpful to highlight several findings from this year and compare them with enforcement activity in prior years. These findings include the following:

- The year 2018 saw the third highest number of cases filed in the last 10 years.

- Civil monetary penalties this past year were the fourth highest since 2012.

- For the first time, the CFTC initiated multiple actions involving virtual currencies after having brought a single action in each of the last two years.

The Big Picture

The CFTC initiated a record high of 102 enforcement actions in 2012. Since 2012, it appeared as though the CFTC’s enforcement activity was trending downward. However, the 83 actions this year nearly doubled 2017’s total. The fact that the number increased should not be surprising. The small number of actions in 2017 could have been due to the CFTC investigating larger and more complex actions that would ultimately conclude in 2018. The difference in civil monetary penalties imposed in these years suggests that this was the case. In 2018, these penalties were approximately $897 million on 83 actions, versus approximately $334 million on 49 actions in 2017. Just six settled attempted manipulation cases resulted in $780 million of the total penalties imposed in 2018. These types of actions were complex and inevitably consumed significant resources in 2017 and, likely, in prior years.

There may be additional factors that contributed to the dramatic increase in enforcement actions. J. Christopher Giancarlo became CFTC Chairman in January 2017 and subsequently appointed James McDonald as the Director of Enforcement in March 2017. Both Chairman Giancarlo and Director McDonald made it clear that the CFTC would not let up on its mission to preserve market integrity. Furthermore, the Division of Market Oversight transferred its market surveillance role over to the Division of Enforcement in mid-2017, enabling Enforcement to see market-disrupting behavior in real time. Another factor contributing to the large number of actions in 2018 may have been market participants availing themselves of the self-reporting and cooperation regime reinvigorated under Director McDonald. Also, the CFTC began to aggressively police the cryptocurrency markets, successfully broadening its jurisdiction over this new and burgeoning asset class. Finally, it is worth noting that 41 actions were initiated in the final two weeks of the CFTC’s fiscal year. This end-of-year push signifies an effort to wrap up a large number of cases before the books were closed on 2018. Whatever the reason, the numbers do not lie — 2018 was a busy year for the Division of Enforcement.

2018 Breakdown

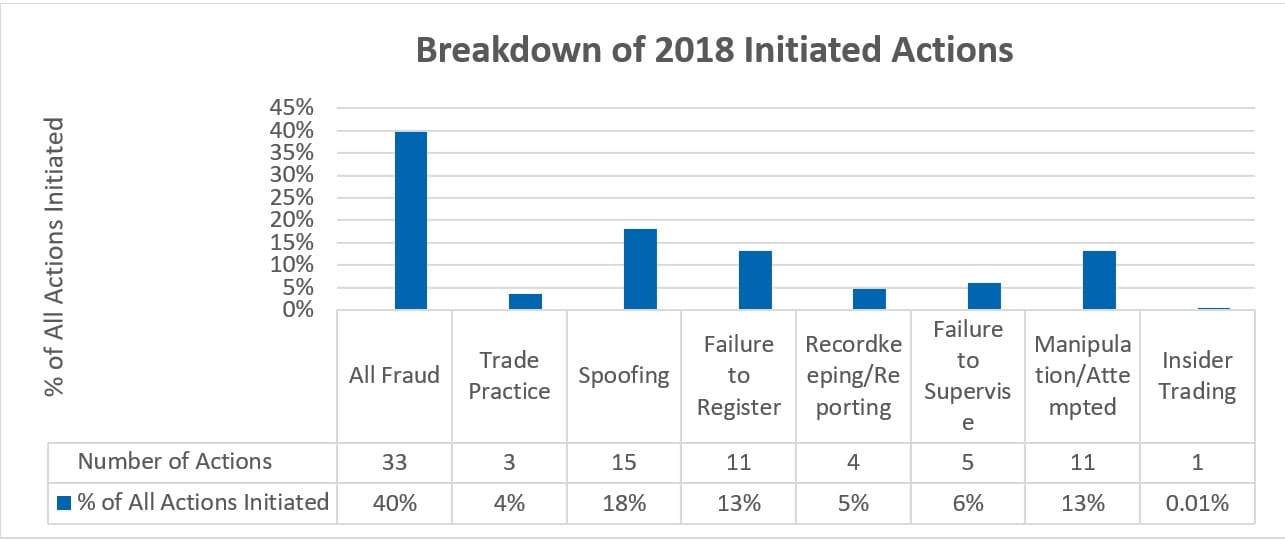

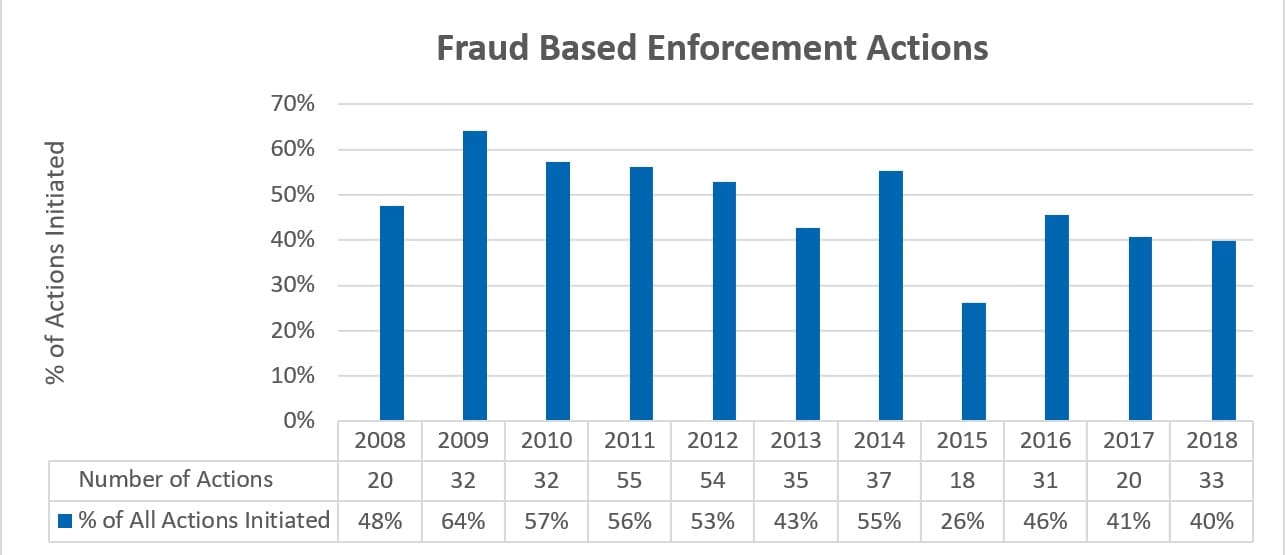

As has been the case for decades, the single largest category of cases initiated in 2018 was nonmanipulation fraud-based actions.[3] Of the 83 actions, 33 were in this category. Of the 33 actions, 11 individuals and five entities were charged for their participation in a binary options fraud ring.[4] Despite the overall increase in enforcement activity, 40 percent of the actions initiated involved nonmanipulation fraud, demonstrating that the Division of Enforcement still dedicates significant resources to stamping out pure fraud in the commodities and derivatives markets.

Similar to last year, the second largest category of cases involved spoofing. The CFTC defines “spoofing” as entering bids and offers “with the intent to cancel before execution.”[5] The 15 spoofing cases initiated in 2018 were six more than were initiated in 2017. By contrast, from 2013 — when the CFTC began bringing charges for spoofing — to 2016, the CFTC initiated an average of just one spoofing case per year. Eight of the 15 spoofing cases from 2018 were brought on a single day and involved three banks and five individuals. In noting the abusive use of technology in these cases, Director McDonald warned that, in addition to prosecuting the individual traders engaged in spoofing, the CFTC holds accountable “those who teach others how to spoof, who build the tools designed to spoof or who otherwise aid and abet the wrongdoing.” In announcing the filing of these actions, Director McDonald credited the Division’s new Spoofing Task Force. The existence of the Spoofing Task Force and the increase in cases brought in both 2017 and again in 2018 strongly signal to the market that combating spoofing is a growing priority for the CFTC.

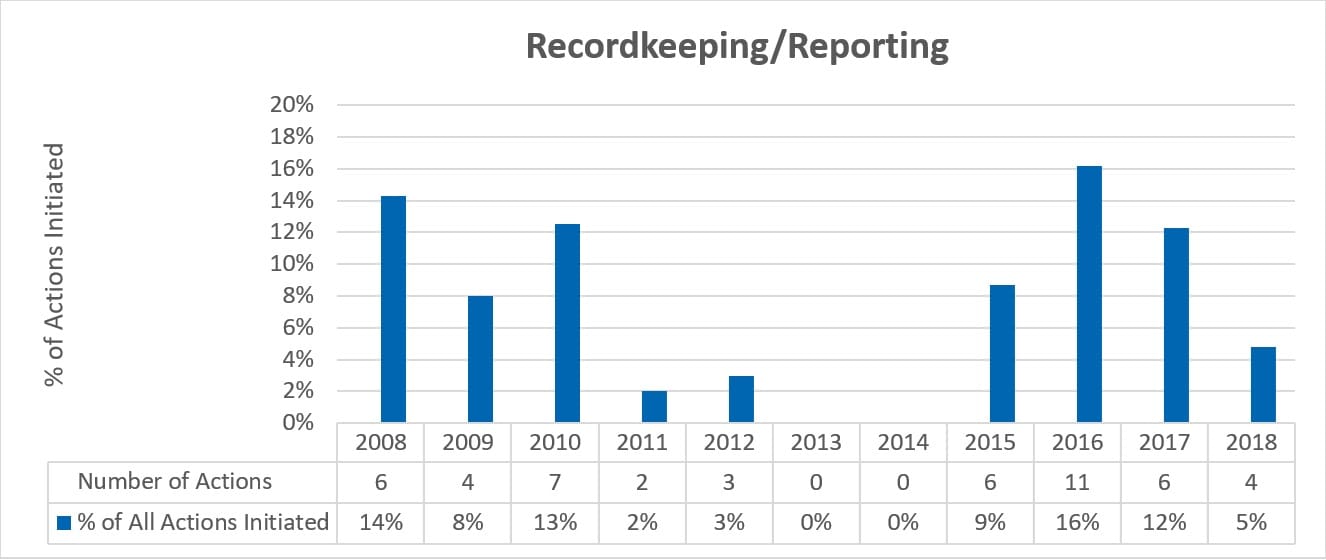

While certain categories of misconduct continued to be areas of enforcement focus, the Division of Enforcement saw a significant decrease in its recordkeeping and reporting actions this year. From 2015 to 2017, an average of 13 percent of all actions initiated were in the recordkeeping and reporting category. The surge in actions that started in 2015 may have been due to the Dodd-Frank Act’s enhanced recordkeeping and reporting obligations, but it appears that the surge is over. Just 5 percent of the cases initiated in 2018 were in this category. Maybe the market got the message and participants improved their compliance efforts and/or the Division of Enforcement’s focus shifted to other priorities.

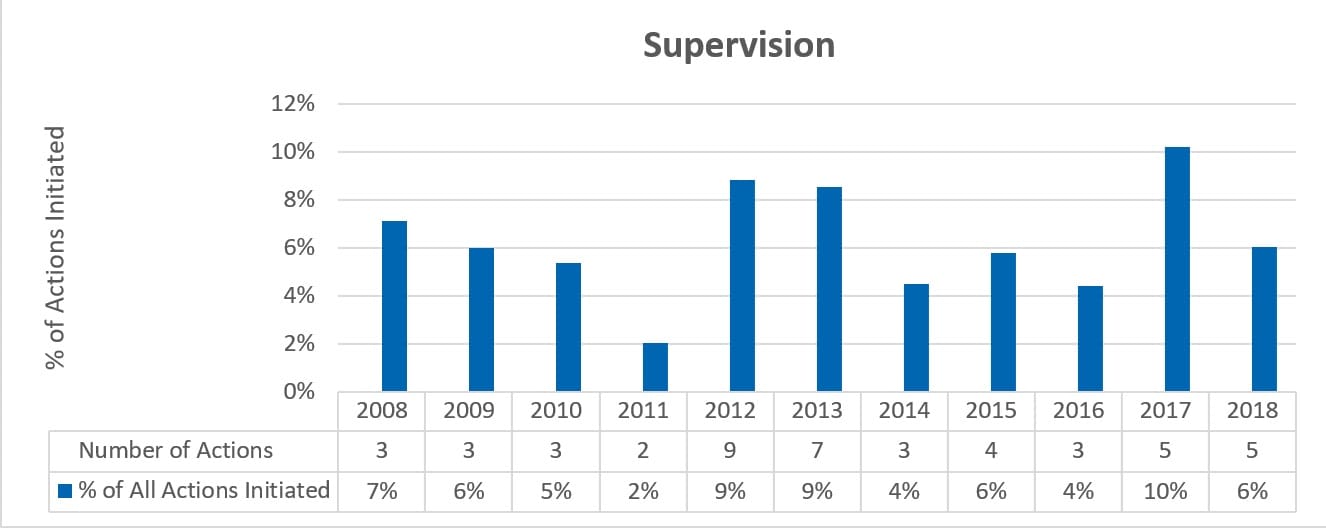

The past year also demonstrated that the CFTC continues to prioritize prosecuting those with supervisory responsibility who fail to adequately fulfill those duties. The five “failure to supervise” cases comprised 6 percent of all actions initiated in 2018. As a percentage of actions initiated per year, the numbers from 2018 are consistent with the average over the last decade.

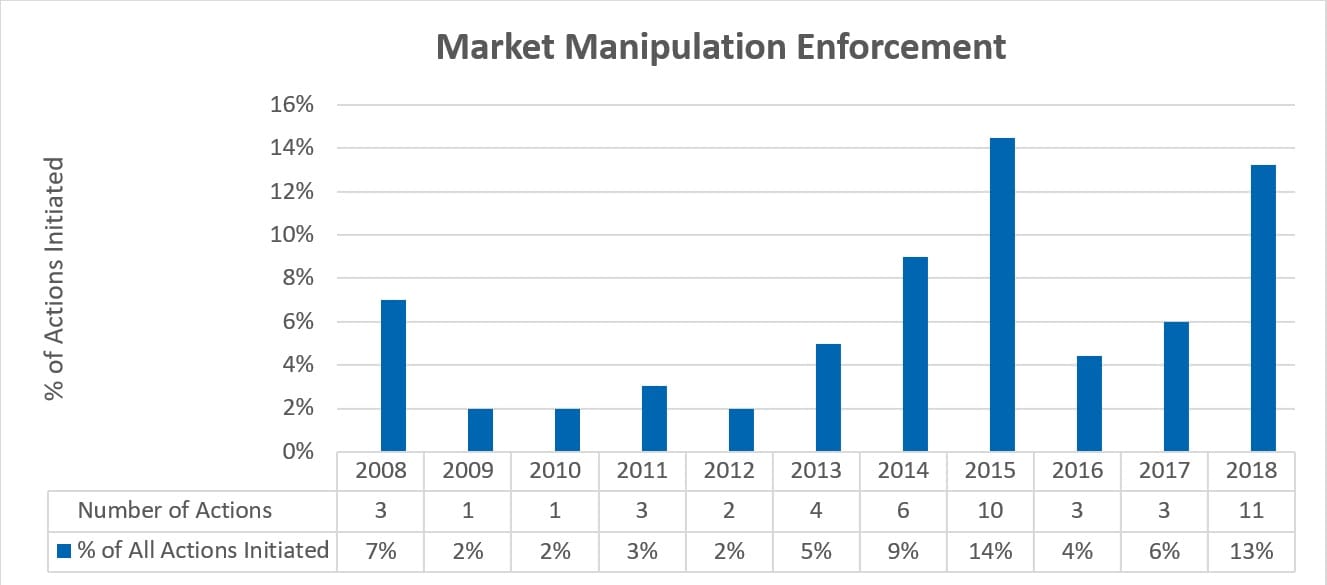

A primary mission of the CFTC is to protect against market manipulation. The CFTC worked toward this mission by bringing the highest number of manipulation (including attempted manipulation) actions in over a decade. Of the 11 actions initiated, five involved attempted manipulation of U.S. dollar ISDAFIX benchmark swap rates and three involved charges of manipulation or attempted manipulation against individuals. Charging individuals with manipulation separately from their employers is not typical for the CFTC. However, it may signal a new trend that would be consistent with Director McDonald’s commitment to not stopping “at corporate charges” by “holding individual wrongdoers accountable for their misconduct.”[6]

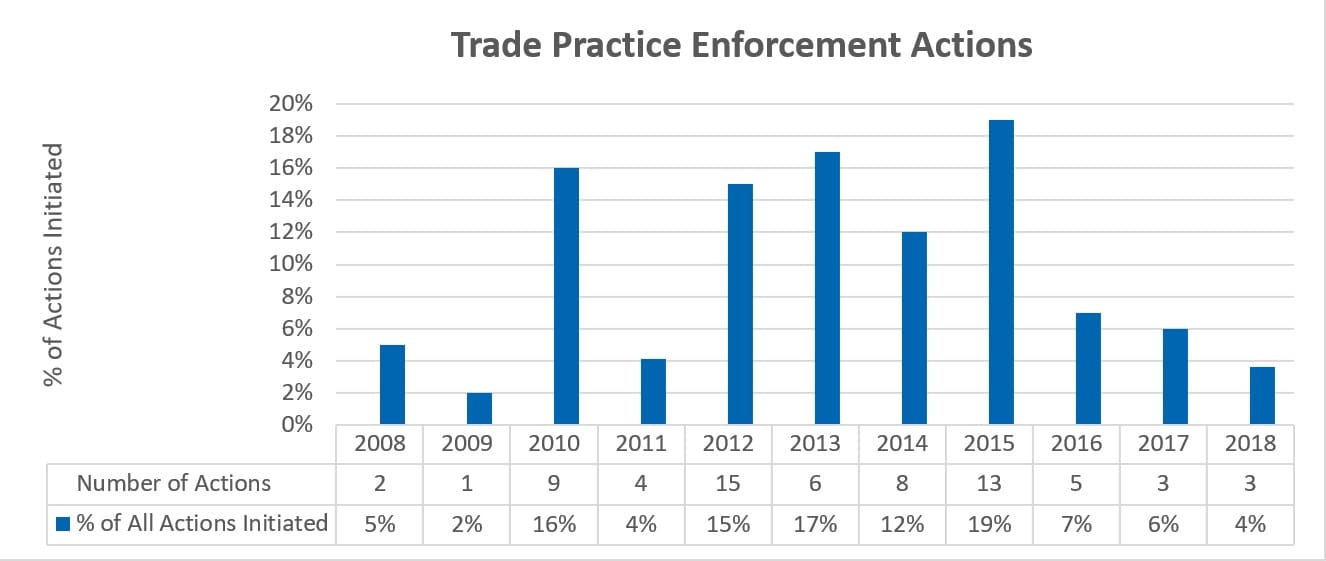

Over the past 10 years, the CFTC brought an average of six trade practice actions per year. However, since 2015, trade practice actions initiated have been trending downward. Trade practice covers a wide range of areas such as position limits, wash trades, prearranged trades, non-bona fide exchange for related position transactions and block trades. Rather than reflecting a lack of interest in these types of cases, the falling numbers may be due to the CFTC’s increasing reliance on exchanges like the CME Group of exchanges and the Intercontinental Exchange to police this type of activity. The CFTC and the CME Group entered into a data-sharing agreement effective February 2019 that will give the CFTC direct access to the CME’s order book data.[7] The data will provide the Division of Enforcement with a greater ability to identify potential violations of the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA), and the arrangement may lead to the CFTC bringing more trade practice actions in the future. Then again, with the CFTC better equipped to look over the CME’s shoulder, the agreement may cause the CME to more aggressively pursue trade practice violations, allowing the CFTC to focus on priority areas, such as disruptive trading and manipulation.

Notable Cases from 2018

Spoofing Setback – U.S. v. Flotron

In January 2018, the CFTC filed a complaint against Andre Flotron, a precious metals trader, alleging that Flotron engaged in manipulative and deceptive schemes to “spoof” orders in the precious metals market.[8] The Department of Justice (DOJ) brought a parallel criminal action against Flotron.[9]

The government alleged that for five years starting in 2008, Flotron manually placed fake orders and swiftly cancelled them to make it appear as if the prices were increasing or decreasing to benefit the orders he intended to execute. Ultimately, the jury found Flotron not guilty of conspiracy to commit commodities fraud, dealing a blow to the government’s anti-spoofing efforts, particularly in light of the fact that Flotron was only the second individual to go to trial on criminal charges based on alleged spoofing trading practices. The first individual, Michael Coscia, was convicted of spoofing in 2015.[10] It is difficult to know why the jury decided to acquit Flotron, but it appears that the government’s case may have suffered from a lack of direct evidence of Flotron’s intent to spoof. The CFTC and Flotron agreed to a settlement of the civil action that will result in a $100,000 fine and a one-year trading ban for Flotron.

Regulating Virtual Currencies

The explosion of virtual or cryptocurrencies created an entirely new asset class that seemingly dropped out of the sky and into the CFTC’s lap. The CFTC is not shying away from exercising jurisdiction over this new market. In a pivotal case, the CFTC brought an action against Patrick McDonnell and CabbageTech, Corp. for allegedly operating a “deceptive and fraudulent virtual currency scheme,” committing fraud through misappropriation of investors’ funds and making misrepresentations through giving false trading advice and promising future profits. The defendants moved to dismiss the complaint by arguing that the CFTC lacked jurisdiction to regulate cryptocurrencies and therefore did not have standing to sue for alleged violations of the CEA.

The court held that virtual currencies fall within the scope of a “commodity” in that they are a “store of value” and serve as a “type of monetary exchange.”[11] The court also analyzed the CEA’s definition of “commodity,” which includes “all services, rights and interests … in which contracts for future delivery are presently or in the future dealt in.”[12] The court ultimately found that virtual currencies can be regulated as commodities under the CEA and that the CFTC has anti-fraud and anti-manipulation jurisdiction over these commodities even if there are no futures or derivatives contracts dealing in the virtual currency at issue. Having successfully defended its jurisdiction, the CFTC is likely to play an increasingly important role in regulating virtual currencies.

Insider Trading in Commodities Markets

The concept of insider trading is usually associated with trading in securities. However, insider trading in commodities is prohibited when the trading is based on nonpublic information gained through deception or fraud or in breach of a pre-existing duty. Once in 2015 and again in 2016, the CFTC sanctioned individuals for using material confidential and proprietary information acquired from their respective employers to trade on their own account. In 2018, the CFTC filed a complaint against EOX Holdings LLC (EOX), a commodities brokerage firm, and one of its brokers, Andrew Gizienski, alleging that the defendants used material nonpublic information about EOX clients to trade on behalf of a customer who happened to be a friend of Mr. Gizienski.[13] All three of these cases rely on a theory of insider trading that prohibits misappropriating material nonpublic information in violation of a pre-existing duty.

The misappropriation and misuse of material nonpublic information is a growing concern for the CFTC. The CFTC recently announced the creation of an Insider Trading Task Force dedicated to investigating and prosecuting violations of the CEA involving misappropriation of confidential information, front running and the use of confidential information to illegally prearrange trades in jurisdictional markets.

Looking into 2019

The incredible growth and the public’s interest in initial coin offerings in the past year suggests that 2018 was the year of cryptocurrencies. These markets got the attention of multiple regulators, and their oversight of virtual currencies will only grow in 2019. The CFTC is expected to move beyond fraud involving virtual currencies to investigating potential manipulation in these markets. The concern about manipulation is real, as evidenced by the reluctance of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to approve a Bitcoin exchange-traded fund due to a perceived risk of market manipulation.[14]

Next year will also likely see increased enforcement in the area of insider trading. The fact that a task force was formed to investigate insider trading strongly signals that the CFTC believes that illegal insider trading is prevalent in the markets it regulates. The fruits of the task force’s work may ripen into enforcement actions in 2019.

Finally, the heightened focus on prosecuting spoofing in 2018 is almost certain to continue into next year. Despite the setback the government suffered in the Flotron case, spoofing is still viewed as a serious problem. The CFTC has given no indication that it intends to be less aggressive when investigating incidents of potential spoofing.

By every metric, 2018 was a year of vigorous enforcement by the CFTC’s Division of Enforcement. Fraud, spoofing and market manipulation actions drove the CFTC’s strong year. There is every reason to believe that these categories of action will be the drivers again in 2019. Whether the CFTC can continue this momentum remains to be seen, but the game changer could be the Division of Enforcement’s cooperation and self-reporting efforts. If a recognizable track record of tangible benefits for self-reporters and cooperators can be established, market participants may be more inclined to work with the Division of Enforcement. This would free up scarce investigatory assets for deployment in other priority areas. Only time will tell if the past year’s zealous enforcement can be repeated.

[1] Gregory Kaufman and Amber Unwala, CFTC Enforcement Actions 2017: “Ye[a]r So Bad? Not The Best Year They’ve Ever Had,” Bloomberg BNA Sec. Reg. & L. Rep. (March 15, 2018).

[2] Speech of Enforcement Director James M. McDonald “Regarding Enforcement Trends at the CFTC, NYU School of Law: Program on Corporate Compliance & Enforcement,” U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) (Nov. 14, 2018).

[3] Fraud-based cases are distinguished from market manipulation cases in this article. Although manipulation cases involve elements of fraud, they are accounted for differently than typical fraud cases involving theft or fraudulent schemes.

[4] CFTC Charges Eleven Individuals and Five Entities in Nationwide Binary Options Fraud Ring, CFTC, https://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/7807-18 (Sept. 27, 2018).

[5] See Q & A – Interpretive Guidance and Policy Statement on Disruptive Practices, CFTC, http://www.cftc.gov/idc/groups/public/@newsroom/documents/file/dtpinterpretiveorder_qa.pdf.

[6] See CFTC Release No. 7804-18 (Sept. 26, 2018).

[7] See CFTC Agency Financial Report at p. 70 (Fiscal Year 2018), https://www.cftc.gov/sites/default/files/2018-11/2018afr.pdf.

[8] CFTC v. Flotron, No. 18-158 (D. Conn. Jan. 26, 2018).

[9] United States. v. Flotron, No. 3:17-cr-00220 (D. Conn. April 3, 2018).

[10] See United States v. Coscia, 866 F.3d 782 (7th Cir. 2017).

[11] McDonnell, slip op. at 19, 24.

[12] 7 U.S.C. 1(a)(9).

[13] CFTC v. EOX Holdings LLC, No. 18-cv-8890 (S.D.N.Y. filed Sept. 28, 2018).

[14] See www.coindesk.com/clayton-sec-ico-funding-security-offering.

Gregory S. Kaufman is a partner at Eversheds Sutherland (US) LLP, where he regularly defends clients in government investigations and enforcement and litigation matters with particular experience in energy and commodities enforcement matters. He is based in the firm’s Washington, D.C. office and can be contacted directly at

Gregory S. Kaufman is a partner at Eversheds Sutherland (US) LLP, where he regularly defends clients in government investigations and enforcement and litigation matters with particular experience in energy and commodities enforcement matters. He is based in the firm’s Washington, D.C. office and can be contacted directly at  Amber S. Unwala is an associate at Eversheds Sutherland (US) LLP where she focuses on an array of business and commercial litigation matters. She is based in the firm’s Washington, D.C. office and can be contacted directly at

Amber S. Unwala is an associate at Eversheds Sutherland (US) LLP where she focuses on an array of business and commercial litigation matters. She is based in the firm’s Washington, D.C. office and can be contacted directly at