with co-author Shawn Henry

The news has been filled this year with reports of ransomware attacks against companies and government agencies, including even law enforcement. Ransomware refers to a type of malware that encrypts or otherwise restricts access to a machine or device. As part of the attack, the attacker will demand that the victim pay a ransom in order to receive the encryption key or otherwise recover access to the compromised machine.

The reality is that ransomware attacks have been proliferating against all types of companies and organizations. Ransomware is a profitable business for underground circles, and we expect to see continued targeting. Because these attacks may be isolated to a single machine, they frequently do not impact a company’s business continuity or result in a noticeable service disruption. In response to an infection, companies may be able to obtain the technical assistance needed to defeat the attack. Free online resources exist that will identify which ransomware infected your system and provide victims with known decryption keys. In other cases, companies may determine that the data loss is not significant and/or that backups exist, allowing them to rebuild the computer by reformatting the hard drive and reinstalling a clean operating system, applications and data. In other cases though, companies pay the ransom.

Ransomware attackers frequently use many of the same tools and tactics, such as spear phishing, as do other hackers. Unlike many hackers, however, ransomware attackers are not focused on stealing data that can be sold or used for illicit purposes (e.g., credit card information and trade secrets). Instead, ransomware is about economic extortion. The attackers prevent a company from being able to access its own system or data, and they make a demand. Usually, they want money, but that could change. Imagine a hacker who holds data and systems hostage in return for the company’s releasing a public statement, making a divestiture or a arranging for a senior executive’s departure? The distinction between routine malware and ransomware is important to manage the scope of the threat. While some companies may not maintain data that is of value to cyber thieves (although that is becoming less and less the case, as evidenced by the proliferation of W-2 tax information phishing attacks), every company is a potential target of a ransomware attack.

There are a couple of reasons why this is such a challenging problem to overcome from a technology perspective. Once the files are encrypted, it is nearly impossible to decrypt them. This leaves the affected organization facing the difficult choice of either paying the ransom or losing their data. In many cases, downtime and data loss are more costly than the ransom, which is why many organizations opt to pay. The second major challenge is that ransomware is highly polymorphic. There are tens of thousands of malware samples and variants detected in the wild.

As a result, all companies should be mindful of the risk of such an attack and take steps to limit the impact of such an attack, including being prepared to respond.

Responding to a ransomware attack can be a stressful and unnerving experience. Not surprisingly, depending on the system that is the target of the attack, time is usually of the essence. As part of a company’s broader incident response preparation, it is worth anticipating what you would do in the event of a ransomware attack. The following five questions are a good starting point for companies, and in-house counsel might consider leading this review together with their information security managers. While the answers to these questions often differ depending on the nuance or nature of a given attack, the investment in planning related to these questions can reduce the stress and increase the agility and effectiveness of a company’s response to an attack.

1. Will you pay the ransom?

This literally can be the million-dollar question, although ransom demands historically have been much smaller. For example, it is common to see ransom demands between $500 and $50,000, typically to be paid with Bitcoin. Regardless of the extortion level, many companies have taken the approach of not negotiating with blackmailers or otherwise paying ransom, regardless of the situation. In fact, the FBI does not encourage payment.

Still, even where there is a general (and understandable) resistance to paying ransom, the answer to this question for most companies will depend on the impact and timing of the attack. That is, the answer frequently depends on the business continuity risk and service disruption potential that the attack presents, as well as whether there is an available and useful backup of the data/service maintained by, or hosted on, the impacted system. More specifically, how badly does your company need the impacted system or the data stored on that system?

For example, if a company cannot access a machine that has critical data for which there is no adequate or available backup, or if the machine is integral to business operation (e.g., a web server or payment service) and there are challenges in replacing the machine in a timely manner, a company may determine that it has little choice but to pay the ransom because the costs of lost access far outweigh the ransom demand. In many scenarios, however, companies have elected not to pay the ransom because they have a sufficient backup of data maintained on the machine or because the lost access to the system does not have a meaningful business impact. For example, from a business continuity perspective, there may be no practical difference between a ransomware attack that locks an employee’s company-issued laptop and the physical theft of that laptop.

Significantly, paying does not always result in the hackers making good on their promise. In a recent case, a hacker only provided partial access to a hospital’s encrypted data before asking for more money to complete the deal. At that point, the hospital refused.

2. What systems are subject to the greatest risk (and are they protected)?

The first question highlights the critical, yet obvious, point that the potential impact of a ransomware attack all depends on which machine, system, or device is hit. It also highlights the fact that ransomware is not just an information security issue, but also a business continuity issue (not unlike, for example, natural disasters). On this point, a company should have the advantage over a ransomware attacker.

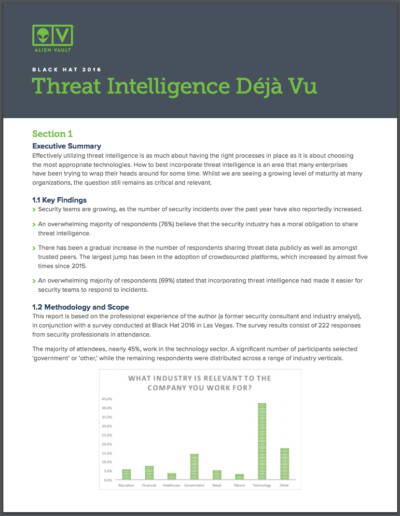

Specifically, a company can assess its systems and dependencies and identify those that present the greatest risk to the company in the event of a ransomware attack. In fact, most companies with business continuity plans will have already gone through this exercise in a more general context. Regardless, once you have identified systems that are critical to your company’s ongoing operations, you then can consider how those systems are currently protected from the types of malware typically deployed in a ransomware attack and whether additional protections make sense. In addition to having appropriate data backup and recovery plans in place, common information security considerations include:

- The use of robust endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions,

- Taking advantage of application white-listing,

- Restricting user permissions and access controls,

- Implementing software restriction policies (SRP),

- Ramping up efforts to detect spear-phishing emails and

- Disabling macros from running in files that are received in email or downloaded from websites.

3. Do you have sufficient backups?

While the previous question was focused on the extent to which critical systems are protected, this question is focused on contingency planning in the event that a company is the victim of a successful ransomware attack. If critical systems are impacted by ransomware, how will your company respond, and will you be able to continue (somewhat) normal business operations? This is an important question, even if your company would consider paying the ransom. For example, even if a company pays the ransom, there will be a loss of data or availability until the key is received and, hopefully, normal access is restored. As a result, from both a data and a systems perspective, it is important to determine the extent of a company’s backups and alternatives that can support business operations. A company should consider not only the extent of its backups, but how frequently those backups are created and tested and whether the backups themselves are susceptible to being encrypted or deleted by the hacker. This will help determine the scope of the data loss at risk in the event of an attack. Similarly, a company should consider its process for restoring data from backup (or switching to backup systems) and whether that process can be simplified or made more efficient.

4. Will you make the attack public?

It can be helpful to consider whether, or the circumstances when, your company would make public that it has been the victim of a ransomware attack. Most companies that have gone public with the fact that they were the victim of an attack appeared to do so because the attack significantly impacted their normal business operations and there was a delay in restoring those operations.

If normal business operations are impacted, there is a question of how you communicate that fact to customers, vendors, business partners and the public generally. For example, if a company will pay the ransom and expects to restore operations within a relatively short time but feels that it is important to communicate to relevant third parties that certain systems are down, does the communication have to highlight the cause of the issue, or can it simply identify the impact? For example, a company could indicate that it is aware of the problem, it is working to address it and when it expects the issue to be resolved. While the nuance of an attack (e.g., the impact and duration) is incredibly important to answering this question, the answer can be equally nuanced. For example, a company may elect to alert third parties only where there is a contractual requirement to do so, keeping in mind that a ransomware attack typically does not include a data breach. Regardless, it is important for a company to consider its communication strategy in the event of an attack. Some companies may even want to take the next step and prepare standby statements that can be used if needed, for example, in response to a third party or even an employee, revealing the incident.

5. Will you contact law enforcement?

A question companies frequently consider in the context of a ransomware attack (and cybersecurity incidents generally) is whether to contact law enforcement and, if so, which law enforcement agency. The answer will be company-specific and depend on a number of factors. Nonetheless, it is important for a company to identify and understand the reasons why it would contact law enforcement in the event of an attack. Not surprisingly, the likelihood of achieving the desired objective varies significantly based on the reason for contacting law enforcement.

A company may contact law enforcement because it wants the attacker brought to justice or because it hopes that there may be technical assistance that law enforcement can provide to help the company regain control of the relevant machine (and avoid paying the ransom). While the facts are always critical, these may not be the primary reasons to contact law enforcement, because the likelihood of law enforcement catching what is likely a foreign actor may be slim; similarly, law enforcement may not have the capability to crack the encryption, and the facts may not warrant law enforcement investing resources in that effort.

A company, however, may contact law enforcement for other reasons. For example, a company may contact law enforcement because, if the attack becomes public, the company can reassure customers, vendors, business partners or even regulators that it did everything possible to respond to the attack. For many types of public cybersecurity incidents, it has become standard for a company to indicate that it has notified law enforcement and is cooperating with the investigation. This also highlights the fact that the company is a victim. In some instances, a company may contact law enforcement because its cyber response policies indicate that law enforcement should be contacted or because it has become standard practice for the company in responding to cyber incidents. A company may also contact law enforcement because the company believes that “it is the right thing to do” as a good corporate citizen. Finally, a company’s cyber insurance policy may require that suspected crimes be reported to law enforcement in order to make a claim for coverage. For each of these reasons, a company may conclude that it is in its best interest to contact law enforcement, even though it believes that the criminal will not ultimately be caught.

The question of which law enforcement agency to contact is heavily dependent on the facts, including the type of company impacted, the threat actor, the type of machine impacted and the nature of that impact; a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this article. For example, if a significant ransomware attack impacts critical infrastructure or a federally regulated entity (e.g., a national bank or an airline), the company should contact federal law enforcement, such as the FBI. If a ransomware attack hits a small hardware store, however, the company should instead consider contacting local law enforcement or using online reporting through the Internet Crime Complaint Center at www.ic3.gov.

Moving Forward

Unfortunately, ransomware is costing businesses hundreds of millions of dollars annually, whether in the form of payments, intrusion response or both. By definition, you cannot prepare after an event. By asking and answering these five questions early enough, you can arrive at a risk posture that is suitable for your business. Hopefully you will never experience a problem. However, should a ransomware incident occur, you will have increased options for managing the event and quickly getting back to business.

Nathan Taylor is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office of Morrison & Foerster LLP. Mr. Taylor’s practice focuses on advising companies on cybersecurity and data incident issues.

Nathan Taylor is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office of Morrison & Foerster LLP. Mr. Taylor’s practice focuses on advising companies on cybersecurity and data incident issues.