In the three years since California implemented its landmark data privacy act (CCPA), more than 20 other states have considered or passed similar rules. 2023 will mark a major shift in the U.S. data privacy landscape, as all four states with new data privacy rules since California will start enforcing their laws this year — starting with the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act, which went into effect in January. IT analyst Alex Tray talks about what makes the new law unique.

Although similar features are typical among privacy laws, compliance with GDPR or CCPA won’t be enough to comply with Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act, which went into effect Jan. 1, 2023. Industry experts have already called the act “a very Virginia” move, representing a special approach to privacy regulations, which is different from both EU GDPR and California’s law.

The new law grants Virginia residents the right to know and decide how their personal data is used by organizations, allowing people to send requests to the organizations holding their personal information, seeking:

- Confirmation of personal information being processed

- Access to their personal data

- Corrections to personal data in case of inaccuracies

- Deletion of their personal data

- A copy of their personal data

- Restriction of processing of their data for the purposes of targeted advertisements, sales of personal data or profiling

Notably, there is no exception to the profiling opt-out, making the VCDPA stricter than the EU GDPR in this regard. Under the VCDPA, an organization must receive a customer’s clear consent to use their personal data for profiling purposes.

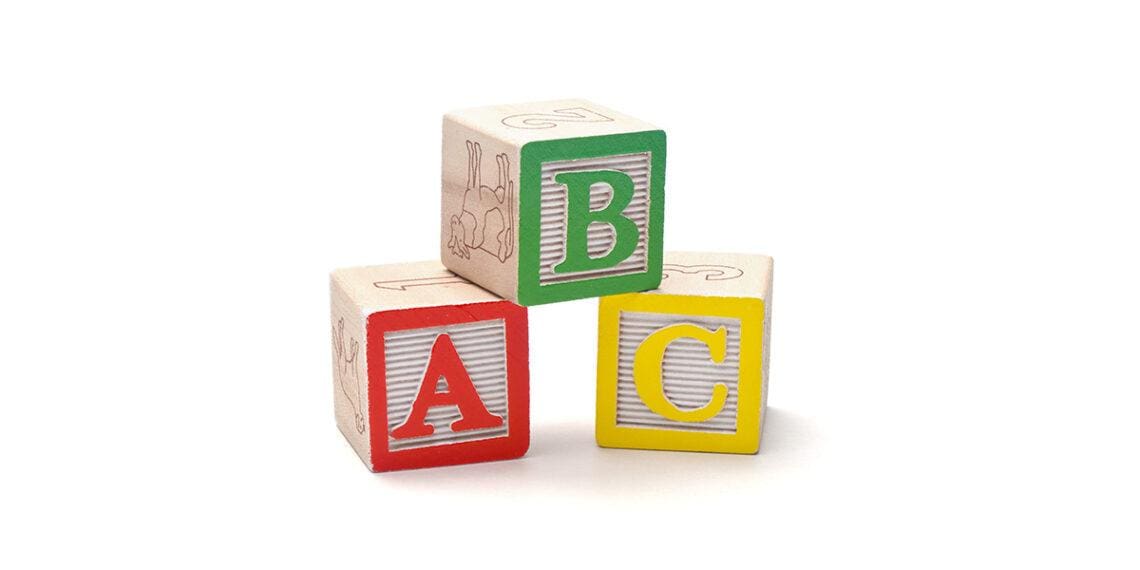

Data Privacy Rules Even a Kindergartener Can Understand

Regulations on consumer data privacy can get complex, but one thing should remain simple: Responsible data governance means simply doing the right thing. Or at least that’s what Osano’s Arlo Gilbert believes.

Read moreA first for U.S. law

Similar to language in the EU GDPR, under Virginia’s law, organizations that must comply are those that “control or process” personal data, and the law defines those terms separately, which makes it unique among data privacy laws in the U.S.

- A controller is an individual or entity that “determines the purpose and means of processing personal data” alone or with other individuals or entities. Under the act, the purpose of a data controller is strictly limited. Consumer data collection is allowed only within the frames of the intended purposes the consumer is aware of.

- A processor, then, is a person or organization that processes data on behalf of a controller.

Virginia requires contracts between a controller and a processor that regulate the processing of consumer data, ensuring that processors maintain required confidentiality levels.

Exemptions & distinctions from CCPA

Nonprofits, entities covered by HIPAA laws, those whose data processing is regulated under the Fair Credit Reporting Act and those covered by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) are all exempted from the VCDPA.

The exemption for financial institutions under the GLBA is worth a separate note. The VCDPA protection is quite broad here compared to other laws, including the CCPA, which exempts only the data that is subject to GLBA, while the Virginia act exempts the entire organization.

Additionally, third-party violations of the Virginia CDPA won’t lead to penalizing the original data controllers and processors. A liability can only be applied when a data controller or processor was clearly aware of a third-party’s violation intent.

The VCDPA demands organizations to provide consumers with the ability to opt-in to personal data processing and to complete every request within 60 days. Ensure that your resources have the necessary disclaimers that a consumer can see — a preliminary filled checkbox doesn’t work here.

Compliance with the VCDPA

Many small businesses are excluded from the CDPA, particularly if they don’t generate significant revenue from the sale of personal data. Organizations are covered if they control or process the data of at least 100,000 consumers, regardless of what they do with the data, or if they handle data for 25,000 consumers and derive more than half their revenue from selling that data.

For companies who should comply with the law but don’t, penalties are far short of the stiff fines they can face for violating the EU’s GDPR, but the Virginia Attorney General’s Office can levy up to a $7,500 fine per violation in the state.

In many ways, the VCDPA is an improvement over the EU’s GDPR, and it goes further than the CCPA in several areas, including prohibiting automated decisions regarding consumer data profiling. Regardless of where they’re based, organizations would be wise to take the opportunity to review their collection and processing of consumer data to adhere to emerging data privacy best practices.

Alex Tray is an accomplished system administrator with a bachelor’s degree in computer science and a decade of experience in IT. He has contributed to the growth of several startups in Silicon Valley and is now a cybersecurity consultant and freelance writer at

Alex Tray is an accomplished system administrator with a bachelor’s degree in computer science and a decade of experience in IT. He has contributed to the growth of several startups in Silicon Valley and is now a cybersecurity consultant and freelance writer at