Compliance doesn’t appear to figure prominently in the update to the Institute of Internal Auditors’ 2013 Three Lines of Defense Model. Compliance consultant Nicole Di Schino takes a look here, providing original reporting for CCI as she shares analysis and opinions from compliance pros and IIA CEO Richard Chambers.

All images courtesy of Institute of Internal Auditors; used with permission

Recent updates to the Institute of Internal Auditors’ (IIA) three lines of defense model offer a refreshing take on corporate governance, but some worry the new model undervalues the compliance function.

Given its authorship, the guidance understandably takes a decisively audit-focused approach, giving thoughtful consideration to how the internal audit team can deliver value. Less attention is paid, however, to the roles of the control functions outside of the audit group – compliance in particular.

IIA CEO Richard Chambers, in an interview with Corporate Compliance Insights, described the changes as simply a remedy to concerns that the original model was so “rigid” that distinctions between the three lines were, in practice, “more like hardened silos.”

Rather than an internal audit function that is “reluctant to reach over and assist management with monitoring and oversight or even sometimes to reach over and be there during the design and implementation of controls,” the updated model stresses “alignment and collaboration,” Chambers said. “There has to be collaboration and communication across the three lines for them to effectively serve the needs of the organization.”

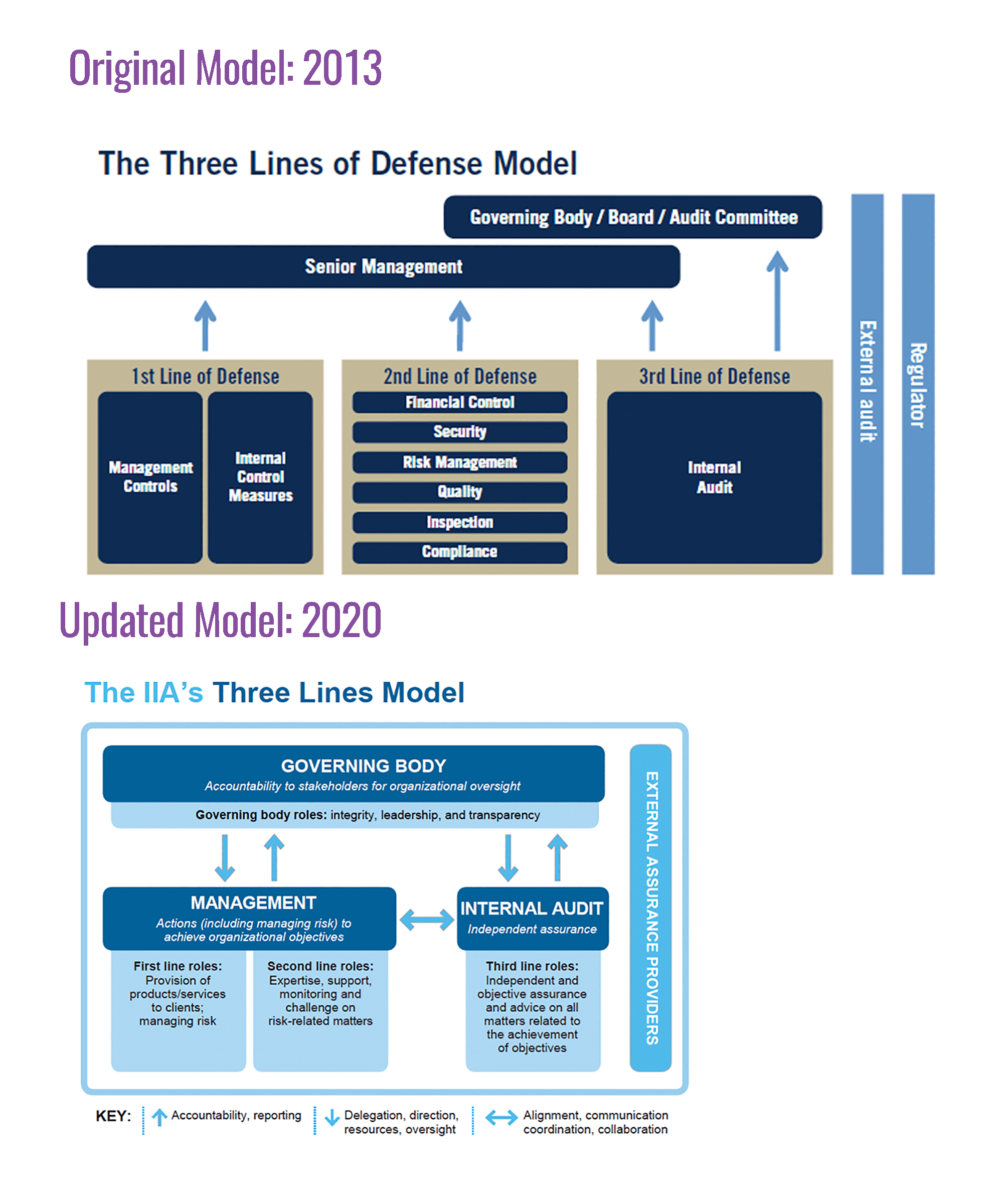

Old vs. New: Comparing the IIA’s Models

The IIA’s original model described three lines of defense against risk — all reporting to senior management — with the third line of defense, the internal audit function, also reporting directly to the company’s governing body, board or audit committee.

Management controls and internal control measures represented the first line in the original model, while the second line included various risk-management functions, including financial control, security, risk management, quality, inspection and compliance.

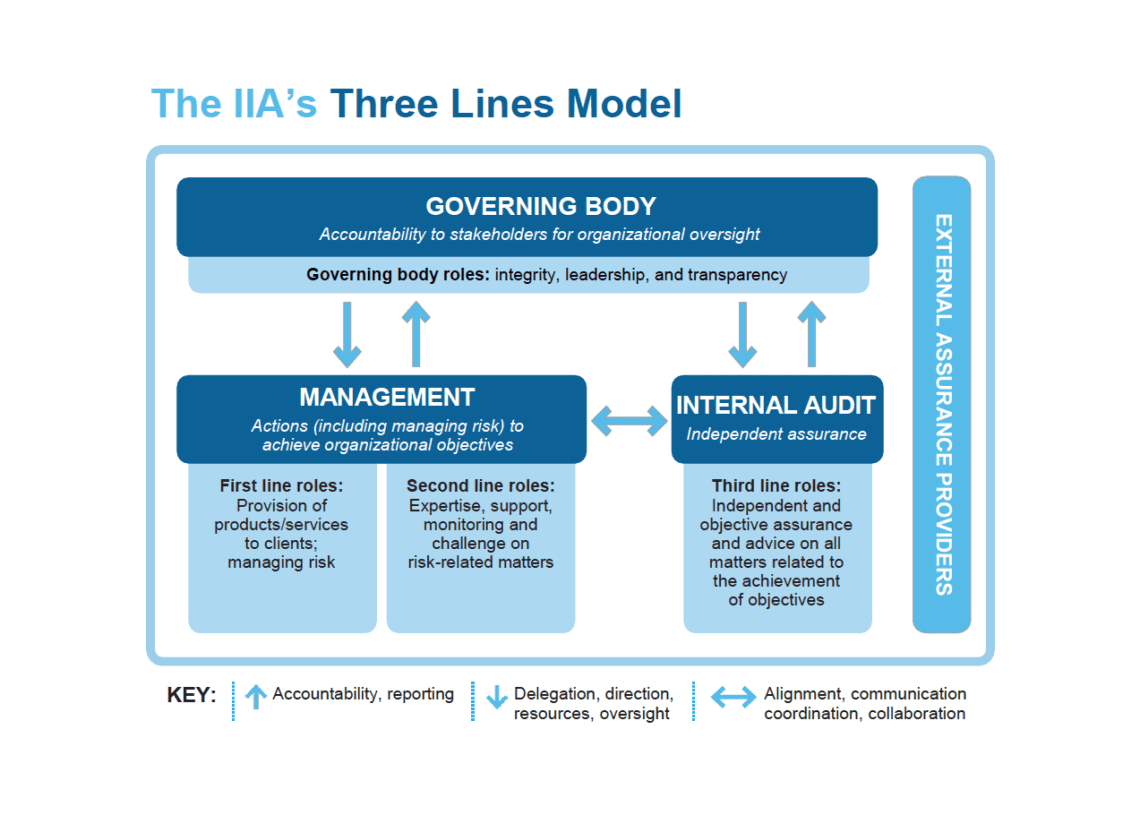

In the new model, both management and internal audit report to and receive oversight from the organization’s governing body.

As stated in its recently published guidance regarding the updated model, the IIA indicates that the new model recognizes that management, compliance and internal audit must work together to mitigate risk, and changes were intended to “identify structures and processes that best assist the achievement of objectives and facilitate strong governance and risk management.”

Companies considering updating risk frameworks in response to the new guidance may be best served by evaluating the guidance with the assistance of all relevant stakeholders, including leaders from management, compliance and audit.

Companies considering updating risk frameworks in response to the new guidance may be best served by evaluating the guidance with the assistance of all relevant stakeholders, including leaders from management, compliance and audit.

Does the New Model Suggest a New Definition of Internal Audit?

The original model’s sole focus on protecting value was also problematic, Chambers, said, since “organizations don’t exist just to protect value, but rather to create value and to serve customers, shareholders and others.”

Internal audit occupies the same space in both models, but the definitions of the first and second lines have changed significantly.

Notably, company management is now deemed responsible both for first-line activities – including managing risk and the provision of products/services to clients – and second-line activities, described as providing expertise, support, monitoring and “challenge on risk-related matters.”

Chambers said he thinks the new model embraces a more modern, expanded view of the role of internal audit, including helping management identify the risks and opportunities that are “out there for tomorrow.”

But does this contemporaneous perspective compromise internal audit’s independence? Chambers acknowledges the skepticism, but both he and the IIA’s updated guidance note that independence was never meant to imply isolation.

“Internal audit has an obligation to collaborate and communicate with management,” Chambers said, a process that starts with “having an internal audit function that has a deep understanding of the business and that has a deep understanding of the roles and responsibilities that management has in making that business successful.”

Auditors also must get comfortable sitting down with management and offering an audit perspective while controls are being implemented, he said.

“If an internal auditor waits until the bridge is built, so to speak, to offer their perspectives about whether it was correctly built, then the value that they add isn’t quite as great.”

Compliance in the New Model – Little More Than a Footnote?

At first glance, it may appear the compliance function has been removed completely from the three lines model. Whereas in the original model, compliance was clearly identified by name as part of the second line of defense, the graphic depicting the new model doesn’t mention compliance at all.

However, the guidance accompanying the graphic states that management, as part of its first-line duties, should ensure “compliance with legal, regulatory and ethical obligations.”

Further, as part of its second-line duties, the guidance gives management responsibility for developing, implementing and improving “risk management objectives,” which would include “compliance with laws, regulations and acceptable ethical behavior; internal control; information and technology security; sustainability; and quality assurance.”

The guidance also states that management may blend or separate its various duties and may elect to assign some second-line roles to specialists to provide “complementary expertise, support, monitoring and challenge to those with first-line roles.”

Ellen McCarthy, Head of U.S. Compliance at Australian stock transfer company Computershare, views the release of the new three lines model as a largely positive development, but says the IIA missed some critical points when it comes to compliance.

“There is a natural difference between the audit perspective and the compliance perspective,” she told CCI. “The IIA is looking at this from the internal audit perspective.”

McCarthy applauds the fact that the new model “recognizes that the second line contributes broad value to the organization,” but says she has reservations about how the model discusses compliance and believes further guidance is necessary.

In contrast, Kortney Nordrum, Regulatory Counsel and Chief Compliance Officer at financial services company Deluxe Corporation, argues the new guidance is consistent with how compliance departments should be viewed.

“Compliance and ethics touch everyone in an organization – and every employee is responsible for understanding their responsibilities from a compliance and ethics perspective,” Nordrum said. “With this update, the IIA has clarified that the responsibility for managing risk remains part of first-line roles and within the scope of management.”

Compliance shouldn’t operate as a second line of defense, Nordrum said. Rather, it should be “woven throughout every role and every function – from the front-line work to the board of directors.”

“This is a win for the compliance function and compliance as a whole,” Nordrum said. “As compliance professionals and owners of compliance programs, we think about ourselves as a function that gives the organization the tools and guidelines to make good choices.”

The Distinction Between Risk Management and Compliance

Still, the shift in the new model from specifically calling out compliance in second-line functions to merely highlighting management’s responsibilities for overseeing compliance causes consternation.

McCarthy worries the new model doesn’t account for “the distinction between the risk-discipline function and the compliance function.”

While risk management deals with risk appetite, compliance is responsible for ensuring that management adheres to all external regulatory requirements and internal compliance and ethics policies, she said.

“It’s very important to recognize those two disciplines and their value to the organization and not lump them all into the concept of risk management,” McCarthy said.

Nordrum is less concerned about IIA’s choice not to name specific departments or functions. By focusing on “the types of support the second line should provide the organization, the new model allows for more flexibility and speaks to a wider audience,” she said.

“It allows smaller organizations without dedicated compliance or risk functions to see how the model can be applied in their non-matrixed organizations,” Nordrum explained, adding that the new model “more accurately reflects how risk is managed in organizations of all sizes.”

So, What IS the Role of Compliance?

McCarthy views as problematic the lack of a clearly defined role for compliance in the model’s second line.

Second-line functions provide value to the organization by performing oversight of the first line, she said. But that responsibility “is not clearly defined in the new guidance.” Rather, it “lumps the second line in with management.”

Nordrum reads the guidance differently.

“By removing compliance from the second line, the new model allows compliance to be absorbed throughout all three lines,” she said, suggesting this “more accurately reflects how compliance should operate in organizations – weaving through everything from the front line to the board.”

Nordrum says any failure to directly address oversight doesn’t trouble her, because she reads the model as consistent with regulatory requirements that the compliance function should audit and monitor the business.

“By reworking the second line and emphasizing the need for the second line to provide expertise, support, monitoring and effective challenge, the new model has clarified and confirmed the role of compliance in advising on and overseeing the proper handling of risk-related matters throughout an organization,” she said.

The Independence of the Second Line

Although the guidance mentions the independence of the second line, “it doesn’t seem to be an integral part of the model,” McCarthy said.

Given that a variety of regulatory agencies, such as the United States’ Department of Justice and the Canadian Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, treat the independence of the compliance function as critical to compliance with specific regulations, McCarthy considers the new model’s lack of specificity to be a serious issue.

Nordrum acknowledges the guidance “really doesn’t speak to independence at all,” but is less concerned.

“Given that the IIA is a professional association for auditors and the three lines model was originally built for the financial sector,” she believes that “functional independence for compliance and audit is baked-in to the understanding of those using and deploying this model of risk management.”

Nordrum also noted regulators’ focus on the independence issue and suggested that companies use a combination of the new three lines model and regulatory guidance to determine the necessary requirements for building and maintaining an efficient and effective compliance function.

Nicole Di Schino is an attorney, editor and compliance consultant. A self-described compliance dork, Nicole has a passion for uncovering and sharing compliance and ethics best practices.

With more than seven years of experience covering the compliance space, she has built a strong network of relationships with compliance experts and brings their varied perspectives to her writing and consulting work. Nicole previously served as the Editor-in-Chief of the Anti-Corruption Report. Prior to that, she was an associate at Quinn Emanuel and Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, where she specialized in white-collar work and civil litigation, including advising companies on building and maintaining compliance programs and responding to government subpoenas. Nicole graduated from New York University School of Law and is a member of the New York bar.

Nicole Di Schino is an attorney, editor and compliance consultant. A self-described compliance dork, Nicole has a passion for uncovering and sharing compliance and ethics best practices.

With more than seven years of experience covering the compliance space, she has built a strong network of relationships with compliance experts and brings their varied perspectives to her writing and consulting work. Nicole previously served as the Editor-in-Chief of the Anti-Corruption Report. Prior to that, she was an associate at Quinn Emanuel and Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, where she specialized in white-collar work and civil litigation, including advising companies on building and maintaining compliance programs and responding to government subpoenas. Nicole graduated from New York University School of Law and is a member of the New York bar.