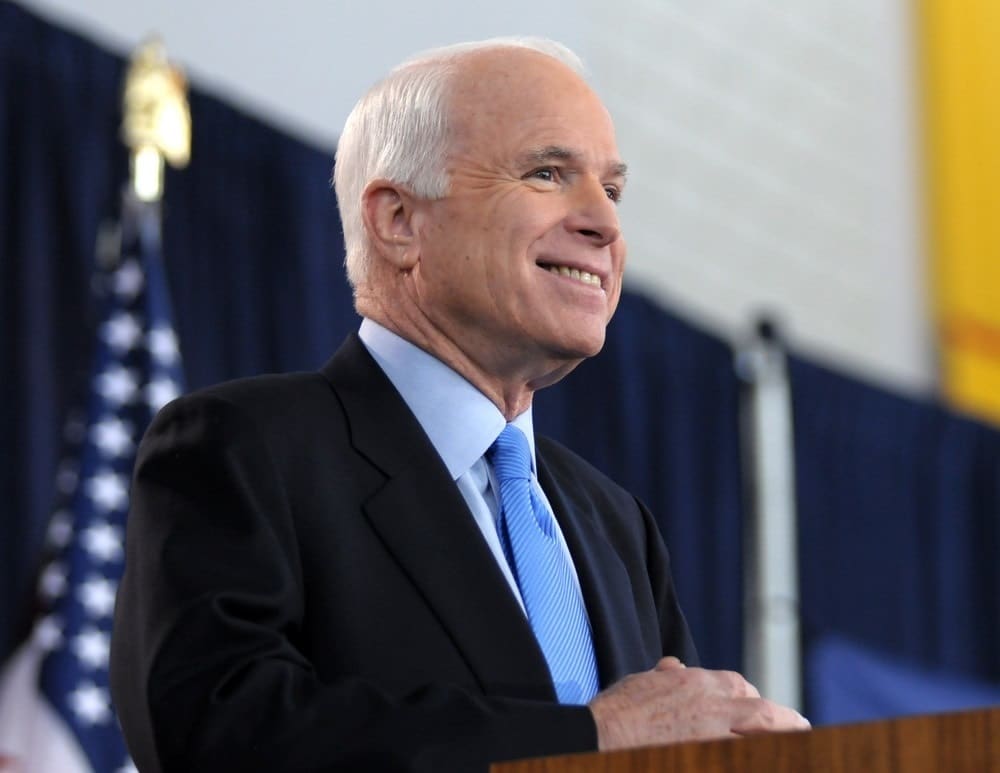

Taking Cues from an American Hero

Linda Henman writes about what set John McCain apart. The virtues he modeled made him an exceptional leader, and the lessons we can learn from his life are well worth every business leader’s attention, regardless of political persuasion.

Why do some people conquer the dragon, but others succumb to it? Why can some overcome adversity when it devastates others? I wanted to know the answer, so in 1995, I decided to study heroes, people who had overcome significant adversity and emerged healthy and hardy — people who had taken care of others while they coped with their own hardships.

I wanted to draw from their experiences in order to advise leaders about ways they can help themselves and others weather the storms that inevitably affect organizations. So, I moved to Naval Air Station Pensacola to study the repatriated Vietnam Prisoners of War at the Robert E. Mitchell POW Center.

Because staggering numbers of military members had suffered Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in previous wars, in 1976, the Navy began to study 138 repatriated Vietnam POWs. In the 20-year follow-up, researchers found that only about 4 to 6 percent of the VPOWs had received a diagnosis of PTSD. (People in most major cities suffer PTSD at about that same rate).

We expected better results with the Vietnam group, but we were astonished by how good the data were. One of the study participants, John McCain, modeled what it took to overcome adversity, return with honor and serve his country for 45 more years.

On October 26, 1967, a surface-to-air missile downed Navy Lt. Commander John McCain III, the son of the four-star admiral who was serving as the commander-in-chief of U.S. Navy Forces in Europe. The Vietnamese did not realize this fact, however, when they fished McCain out of Western Lake with two broken arms and a broken leg.

Ashore, McCain’s captors smashed a rifle butt into his left shoulder, breaking it, and bayoneted a wound into his left foot. The captors then tortured McCain for intelligence, as they had done with the other captured POWs. When McCain refused to comply, the captors retaliated by refusing him adequate medical treatment for his injuries.

Soon, the guards learned that they had captured “The Crown Prince,” a name given McCain because of his father’s rank and position. The guards treated all the prisoners brutally, but they were less harsh with McCain after that. They wanted to use him as a propaganda tool by offering him his freedom. McCain refused. He wrote later, “I knew my release would add to the suffering of men who were already straining to keep faith with their country. I was injured, but I believed I could survive. I couldn’t persuade myself to leave.” The captors repeated the offer of early release eight months later. Once again, McCain rebuffed them, but that time he paid a huge price for his decision — a decision that meant five more years of captivity, torture, isolation and starvation.

The participants in my study told me that there were four main forces in the POWs’ lives that helped them remain resilient: a belief in God, patriotism, a dedication to each other and a sense of humor. They and McCain also taught me what it takes to lead during adversity.

At the time of his capture, McCain was only 31, yet he proved leadership involves more than age, title, rank or position. He served as role model for others about what it takes to live a code of conduct and to behave with integrity.

During his campaign for the presidency, he showed us that civility must define leadership. When a woman at one of his rallies attempted to disparage then Senator Obama, Senator McCain took the microphone from her and let all of us know that he didn’t intend to sink into a type of jungle mentality during the campaign.

While serving in the Senate, he made numerous unpopular decisions, even ones that drew the ire from his own party. He taught us that a person can disagree without being disagreeable.

During one of his last interviews, he described himself as “the luckiest man.” Despite the adversity he suffered early in his life, the pain of living with the injuries he sustained in prison, the disappointment of losing the presidency twice and the harsh knowledge that he was being ravished by cancer, Senator McCain refused to be a victim, and he taught us the importance of refusing to be one, either.

While doing my research, I met Senator McCain twice. Both times I knew I was in the presence of an important man and a really funny one. To prevent a disjunction of the self and to find meaning in a situation void of meaning, the VPOWs relied on resources many of them did not know they had. One of those coping skills was a sense of humor, and McCain demonstrated a well-developed one.

On August 25, 2018, America lost a person the media have called a patriot, hero and statesman. Arguably, he personified all those, but I’d like to add leader and teacher to the list, because he modeled for us what these two titles can and should be. He adhered to the military’s code of conduct while he was in prison, but he also lived by an internal code throughout his life. Of all the leadership lessons, this stands as the most relevant and important.

Dr. Linda Henman is one of those rare experts who can say she’s a coach, consultant, speaker, and author. For more than 30 years, she has worked with Fortune 500 Companies and small businesses that want to think strategically, grow dramatically, promote intelligently, and compete successfully today and tomorrow. Some of her clients include Emerson Electric, Boeing, Avon and Tyson Foods. She was one of eight experts who worked directly with John Tyson after his company’s acquisition of International Beef Products, one of the most successful acquisitions of the twentieth century.

Linda holds a Ph.D. in organizational systems and two Master of Arts degrees in both interpersonal communication and organization development and a Bachelor of Science degree in communication. Whether coaching executives or members of the board, Linda offers clients coaching and consulting solutions that are pragmatic in their approach and sound in their foundation—all designed to create exceptional organizations.

She is the author of Landing in the Executive Chair: How to Excel in the Hot Seat, The Magnetic Boss: How to Become the Leader No One Wants to Leave, and contributing editor and author to Small Group Communication, among other works.

Dr. Henman can be reached at

Dr. Linda Henman is one of those rare experts who can say she’s a coach, consultant, speaker, and author. For more than 30 years, she has worked with Fortune 500 Companies and small businesses that want to think strategically, grow dramatically, promote intelligently, and compete successfully today and tomorrow. Some of her clients include Emerson Electric, Boeing, Avon and Tyson Foods. She was one of eight experts who worked directly with John Tyson after his company’s acquisition of International Beef Products, one of the most successful acquisitions of the twentieth century.

Linda holds a Ph.D. in organizational systems and two Master of Arts degrees in both interpersonal communication and organization development and a Bachelor of Science degree in communication. Whether coaching executives or members of the board, Linda offers clients coaching and consulting solutions that are pragmatic in their approach and sound in their foundation—all designed to create exceptional organizations.

She is the author of Landing in the Executive Chair: How to Excel in the Hot Seat, The Magnetic Boss: How to Become the Leader No One Wants to Leave, and contributing editor and author to Small Group Communication, among other works.

Dr. Henman can be reached at